Applecore: The Smiths, De La Soul and Erykah Badu

Our journey through Apple Music's top 100 Albums of all time continues.

Liz and I are listening to Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums of All Time. One album a day-ish, counting down to number one. We did this with Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 Albums of All Time, and it took more than a year. This should only take a hundred days or so. I’ll be posting a few thoughts here as I listen. We’ll be dropping standout tracks from the listen on this Spotify playlist here.

Here’s parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight and nine.

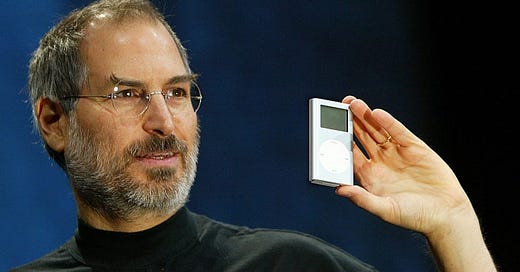

66: The Smiths — The Queen Is Dead

I was talking to a friend about the Smiths recently and she said that being a Smiths fan is a necessary stage of life, but it’s also necessary to get out of it. “You’re crazy if you’re never a Smiths fan, but you’re crazy if you’re still a Smiths fan” was how she put it. (Or, as my wife has it: “Sometimes the Smiths sound a little too much like the Smiths.”) There’s something to that.

In the 1980s, a whole lot of people found themselves in the former category: crazy for never being Smiths fans. Morrissey took that personally. He believed his band was the heir apparent to the Beatles, and was not above blaming everyone’s failure to grasp it on a vast label conspiracy. (“In essence, [other, non-Smiths] music doesn’t say anything whatsoever,” he once said. “It’s an absolute political slice of fascism to gag the Smiths.”) To be fair, Morrissey wasn’t totally alone in believing the Smiths were pop rock royalty. There were a slew of critics and diehard fans who knew the Smiths were something special. But there weren’t enough of them to elevate the band’s singles past the middle of the charts.

You can hear Morrissey’s irritation about this on The Queen Is Dead, which serves as both snotty middle finger to the aristocracy, self-pitying ode to unrequited love and grandiose meta-commentary on the Smiths’ own place in the cultural zeitgeist. The middle finger part is the Smiths’ attempting to resurrect the glory days of British punk. The self-pitying odes is the band angling for pop music relevance. The grandiose meta-commentary is all Smiths, and it’s where Morrissey wallows in his campiest, most aggrandizing proclivities. That sounds like a criticism, and maybe it is. But the weird alchemy of Morrissey’s blustery falsetto and Johnny Marr’s honeyed guitar work makes it all go down beautifully. Here, at least, the Smiths do have something in common with the Beatles: they remain compelling even at their most ridiculous.

Morrissey and Marr met at a Patti Smith show. They hit it off over a shared love of poetry and the New York Dolls, and exchanged information. So the next day, Marr went over to Morrissey’s house with a proposition: would he be interested in starting a band? He was. They later picked up Marr’s friend Dale Hibbert to play bass and auditioned Mike Joyce onto the drumkit. Geoff Trade, the legendary founder of Rough Trade Records, signed the band himself, beginning a long and deeply unhappy relationship that finally came to its welcome end in ‘87.

Artists trying to take a step back and publicly assess their place in the narrative is a dicey prospect. Sometimes you get Kanye’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. Sometimes you get Taylor’s Reputation. With The Queen Is Dead, you get Fantasy’s egoism and Reputation’s melodrama all in one golden stew. Morrissey knows that “fame can play hideous tricks on the brain” but would still “rather be famous than righteous or holy.” He knows “how Joan of Arc felt” but still insists that his most provocative statements are “only joking.” At his most desperate, he wails “how can they hear me say these words, and still they don’t believe me?”

There’s plenty of melancholy to go around on this album, and basically every sadcore band of the past 40 years owes something to the Smiths. But the emotional palette is more diverse than the Smiths get credit for. “Cemetry Gates” has an amicable bounce to it and “Frankly Mr. Shankly” is wryly petty while lightly evoking Sgt. Peppers levels of melodic playfulness. And of, course, “There Is a Light That Never Goes Out,” which really does capture Morrissey and Marr at the peak of their respective talents. Morrissey, overwrought, self-aware and, in the end, sincere in his longing to die by your side. Marr, nimbly soaring over the wreckage of a double decker bus, sweet with just the slightest dash of bitter. It’s all so beautiful that all of a sudden the “best British band since the Beatles” stuff doesn’t sound so insane. You’d be crazy to never get into this band.

They split up just a few years later for reasons that nobody involved has ever fully explained. Morrissey and Marr’s respective solo careers have had their share of good songs, but they’ve also made it clear how much these two guys sharpened each other. Interpersonally, of course, Morrissey’s reactionary petulance has blossomed into total insufferableness, which led plenty of teen Perks of Being a Wallflower readers and 500 Days of Summer watchers to cut their time as a Smiths fan short. You can hardly blame them.

A few years ago, somebody asked Nick Cave about separating Morrissey the Far Right Blowhard from Morrissey the Stirring Artist, and Nick took that seriously. He called Morrissey “arguably the greatest lyricist of his generation” but acknowledged “how upsetting Morrissey’s views may be to the marginalized and dispossessed members of society, or anyone else for that matter.” On the subject of separating the art from the artist, Cave argued that once a song is released to the public, that separation has already been taken care of. “When I write a song and release it to the public, I feel it stops being my song,” he says. “It has been offered up to my audience and they, if they care to, take possession of that song and become its custodian. The integrity of the song now rests not with the artist, but with the listener.”

Cave continues: “We should thank God that there are some among us that create works of beauty beyond anything most of us can barely imagine, even as some of those same people fall prey to regressive and dangerous belief systems.” This is a pretty sensible way of thinking about good art created by bad people, and will probably be a useful thing to keep in mind for some other upcoming artists on this list.

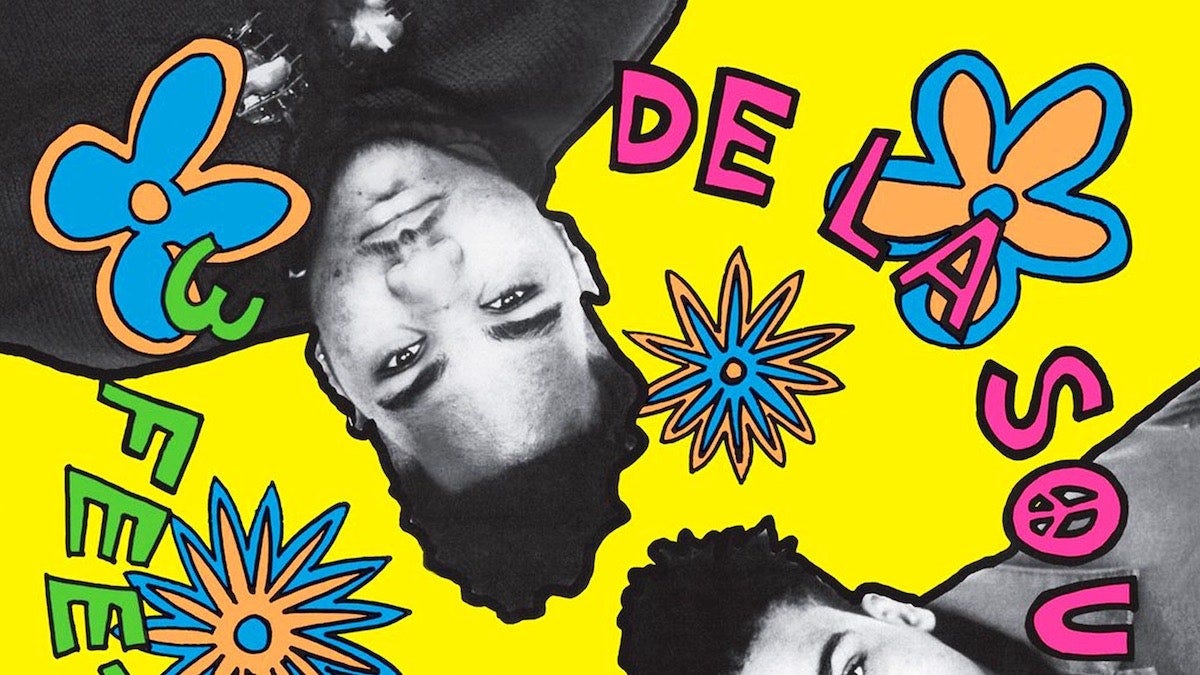

65: De La Soul — 3 Feet High and Rising

AI art is all about that mashup life. What if Studio Ghibli made the Matrix? What if Cormac McCarthy wrote The Cat in the Hat? What if Sabrina Carpenter sang Bohemian Rhapsody? This “What if X did Y?” AI prompt energy even became a brief player in the Kendrick/Drake beef, when Drake used AI to make it sound like Kendrick’s hero Tupac delivered a diss verse from beyond the grave. Drake was rightfully excoriated for this braindead stunt and yanked the track with his tail between his legs after Pac’s estate threatened legal action. I’m not smart enough to understand all the copyright stuff surrounding that, but I can tell you that it’s creatively bankrupt.

I do not understand why Drake thought using AI to make a voice that kinda sorta sounded like Tupac would land a killing blow, but I understand the artistic impulse to put two seemingly unrelated things in conversation with each other. It’s the reason I find the White Stripes’ cover of “Jolene” or Mike Mignola’s “Gotham by Gaslight” so much fun. You put two seemingly unrelated things together, magic can happen. At its best, these two things not only enhance or contrast against each other in interesting ways; they make a whole new kind of thing. That’s what happened with 3 Feet High and Rising.

In the ‘80s, hip hop was on a collision course with destiny, and its smartest minds were starting to explore the limitations of this young artform. Marley Marl was goofing around in his studio and accidentally invented sampling and, with it, ushered hip-hop into a new stratosphere of possibilities. With Marl’s innovation, rap music — which had thrived in the pure improvisational immediacy of the moment — now had the entire history of recorded music at its disposal. A lazier generation of artists would have used sampling as a crutch, but the early ‘80s hip-hop scene was pulsing with creative verve and daring. And few artists were more daring than De La Soul.

They met at Amityville Memorial High in the Black Belt of Long Island. Kelvin “Posdnous” Mercer, Dave “Trugoy the Dove” Jolicoeur and Vincent “Pasemaster Mase” Mason were all cerebral pop culture obsessives with oddball interests and encyclopedic commands of their parents’ and grandparents’ record collections. The trio found a kindred soul and ringleader in “Prince Paul” Huston, who brought not only dizzying wordplay but an eye-popping record collection to the table. Together, the trio (which was really a quasi-quartet) set about a series of studio recording sessions of one upmanship, each trying to out-obscure the other with deeper and deeper pulls from dustier and dustier record bins for a sample that would make the track sing. In fact, their label would later hold a listener contest, offering $500 to the first fan who could name the sample used on “Plug Tunin.’” The prize went unclaimed for months. (It was from the Invitations’ “Written on the Wall.”)

All this makes it sound like De La Soul were pretentious nerds, which is true, but also reductive and a pretty big disservice to their vibe. Yes, they were bohemian outsiders, a brainier take on the brawny vibe of their West Coastal hip-hop contemporaries. But Trugoy, Mase and Posdnous are funny dudes, and their goofball humor is the grease that makes all their heady technical wizardry go down like honey. From the gameshow framing device that holds 3 Feet High and Rising together to the sing-song playfulness of proper opener “The Magic Number” to forever party anthem “Me Myself and I,” De La Soul were not presenting as tortured artists. They were clearly having a ball with all this. It was so fun and exciting that the Beastie Boys reportedly listened to 3 Feet High and Rising together and considered scrapping their own nearly finished Paul’s Boutique and starting over. That playful spirit of excellence extended to the range of music they pulled from for sampling.

In 3 Feet High and Rising, Steely Dan could jam with Otis Redding and the Mad Lads. Hall and Oates could record a song with the Detroit Emeralds. De La’s genius brought Black artists like the Jarmels and the New Birth into the studio with white artists like Billy Joel and Led Zeppelin. They used a learn-to-speak French record. They used the Schoolhouse Rock theme song. They used a Liberace cassette tape they found in the studio. An Eddie Murphy sample shows up on “The Magic Number” just a few seconds before a Johnny Cash snippet reveals the album’s title: “How high’s the water, mama? Three feet high and rising.”

And all this was spun through the group’s unique sonic sensibility. These guys weren’t just throwing two song clips together to see what happened. They were painting a new world, creating their own lingo and forging their own identity. Time itself was their instrument, and they ran wild with its potential.

At the time, this was all legally the wild west. Only recently has De La Soul’s catalog been made available on streaming services, since the label itself was initially too skittish to clear the samples and has since been too lazy to bother. De La Soul actually volunteered to do all the backend work on their own, but Warner brushed them off, clinging to the rights even as they denied the artists any ability to profit off their own work. Thus, this enormously consequential album spent decades all but unavailable, leaving fans in a lurch and new generations unable to appreciate the vast scope of its legacy.

Fortunately, this was all rectified last year, and not a moment too soon. Whatever its potential uses, one of the enormous downsides of the proliferation of AI art has been giving people the ability to feel like they’re being creative without actually doing any creative work. The results speak for themselves. 3 Feet High and Rising is a joyous, jubilant showcase for what is possible when you see the work of what came before not as a shortcut for making your own art, but as an invitation to enter into a wider world of invention.

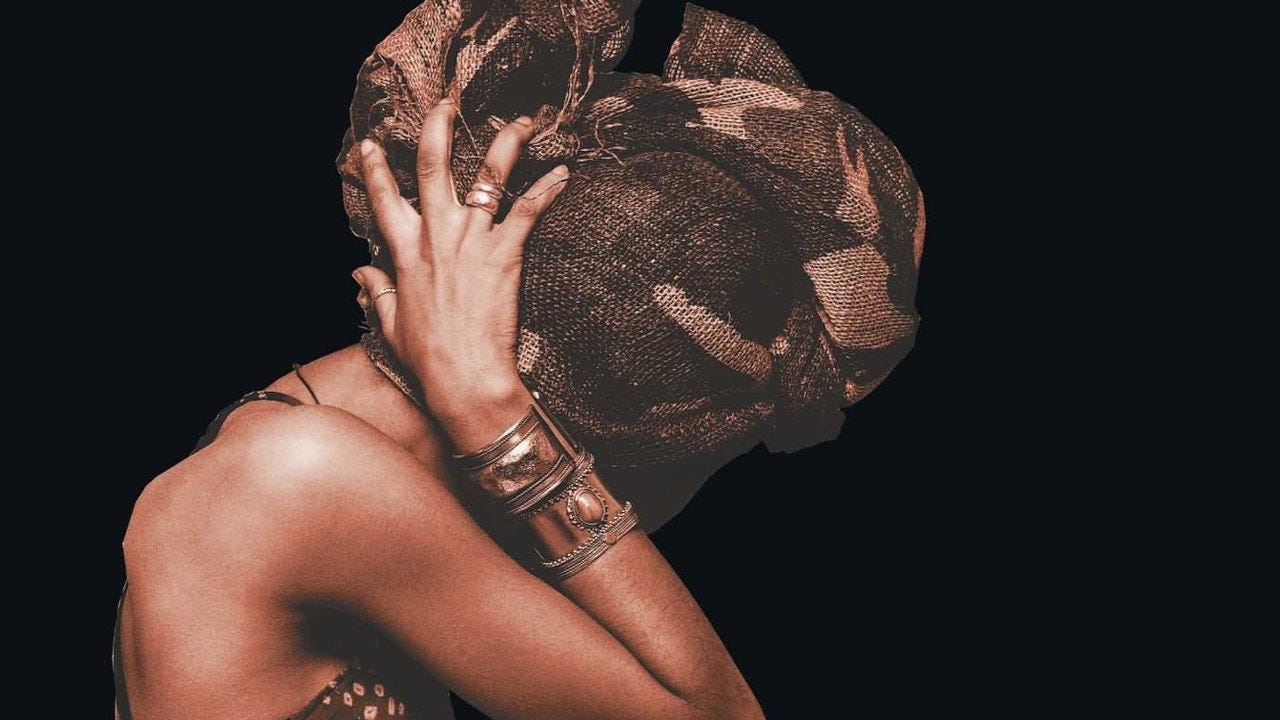

64: Erykah Badu — Baduizm

Erica Wright was a teenager when she changed her name to Erykah Badu. She would later say that she considered “Erica” to be a slave name, and swapped the “-ca” out for “kah” — the Egyptian word for soul. Meanwhile, she just loved “ba-du” as a jazz scat sound so much that she made it her new last name. These drives — social awareness, spiritual practice and sonic inventiveness — would charge the rest of her personal and creative life.

You can see the sonic inventiveness from the very first track on her debut. In 1995, she was 24 years old, recording Baduizm and called her producer to ask him what that “tick-tock” sound on a drum was. He told her it was a rim shot. She created a whole rhythm of rim shots, and then wrote a song around it called “rim shot,” which ended up bookending the album. This is how she makes music: on instinct, impulse and inspiration. But that spirit of spontaneity was expertly captured and molded into shape by Badu and her crackerjack band — a band the world would come to know as the Roots. The result is a golden line through the history of Black music, from ‘30s Gospel to ‘70s jazz to ‘90s R&B and off into the new millennium Badu herself was building.

In ‘97, Badu was part of a braintrust of socially and spiritually attuned artists calling themselves the Soulquarians. This group included the Roots and other luminaries like D’Angelo, Black Star and J Dilla. Many members of the Soulquarians went on to have enormous careers, and I’m sure we’ll see a few of them on this list in the near future. But Baduizm was the first volley from the underground into the mainstream. It went double platinum, and clinched the Grammy for Best R&B Album of the year. It brought “neo-soul” to the masses, and no matter how divisive that genre ended up being (Badu herself has seemed uneasy with the label), it was a briefly useful tool for the rest of the world to get a handle on just what was happening here.

Badu was clearly inspired by the analog age, and Baduizm is infused with a sepia, lived-in luster that beautifully compliments her voice’s slight Texas twang. But she was no iconoclast. Tracks like “Next Lifetime” and “Sometimes” course with Afrofuturistic energy, like a vinyl listening party on the moon.

It was the music of soul-searching, the sound of being more aware of the workings of the world by freeing your mind. These were lush, richly textured jam sessions that directed political awareness towards self-love and liberation. It pulled from guys like Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, whose social commentary was deeply intertwined with their own personal journeys with love, heartbreak and community. But Badu, who was born around the same time as hip-hop and got her start opening for guys like Tribe Called Quest and Naughty by Nature, knew how to bring a thrillingly immediate vibe to this classically attuned romp. “Appletree,” which is dedicated to “all the creative, righteous children,” is a simple ode to the pleasures of good company and the importance of picking good friends. “Next Lifetime” charts the struggle of releasing someone you’re in love with. She approached these topics like a philosopher everywoman, a relatable seer navigating life’s thorniest issues with a little extra wisdom.

This would all become central to her public persona, and fans would elevate her into a bohemian Gaia. Badu was not above accepting these accolades, but her spiritual empathy was informed by both African scholarship and aesthetics. She challenged her fans to think beyond the system and to question the status quo. Follow-up albums would be more overtly political, but Baduizm’s personal is political and vice-versa, a circuitous path. It ends the same way it began — with a rimshot of passion, precision and pure creative expression. The only thing for a listener to do is to take it from the top.