AppleCore: Nine Inch Nails, Steely Dan, SZA and Kraftwerk

Our journey through Apple Music's Top 100 Albums of All Time continues

Liz and I are listening to Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums of All Time. One album a day-ish, counting down to number one. We did this with Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 Albums of Al Time, and it took more than a year. This should only take a hundred days or so. I’ll be posting a few thoughts here as I listen. We’ll be dropping standout tracks from the listen on this Spotify playlist here.

Here’s parts one, two, three, four, five, six and seven.

74: Nine Inch Nails — The Downward Spiral

I loved the first episode of The Bear’s third season. It was a swing, for sure, but it was the sort of swing that comes from a supremely confident group of writers who are really feeling themselves. 'Carmy: The Tone Poem' functioned more as a portrait of a man in crisis than actual narrative development, but the faith this show put in its performers (not to mention its audience) to go with the material ended up being very beautiful and affecting. Halfway through, my wife and I both remarked that it wouldn’t have worked without the music. I was not surprised when I learned who was behind it.

Trent Reznor’s career reinvention as a go-to guy for scores is one of those things that nobody would have guessed ahead of time, but makes total sense in hindsight. Reznor was always a keyboard guy, and Nine Inch Nails was always a synthpop band in industrial trappings. Reznor grew up as a big fan of acts like the Human League and Gary Numan, and he deployed their melodic principles to a new kind of quasi-metal. It’s not hard to see how he could (and has) used those same instincts to create some of the best movie scores of this decade. But before The Social Network and Challengers, there was The Downward Spiral. You take the NIN equation and add a frontman with Reznor’s theatrical charisma, you’re going to get something special. And The Downward Spiral is definitely special.

Trent Reznor grew up with his grandparents in Pennsylvania. He was a good kid, a Boy Scout who loved the piano and model planes. His grandpa told People Magazine that “music was his life.” Reznor recalls feeling a little cooped up by his small town, and was inspired to use music as his way out after seeing the Eagles live in ‘76 (this is the second time someone on this list who I like has been inspired by the Eagles, who I don’t. I am not revising my opinion on the Eagles.)

A couple early music projects went nowhere, and Reznor struggled to find musicians who could bring the music he was hearing in his head to life. The lightbulb went on when he heard that Prince played all his own instruments. He cut a demo all by himself and the labels liked it. Nine Inch Nails was born and Pretty Hate Machine dropped in ‘89.

In the early 90s, rock and roll stardom was in a tough place. It killed Kurt Cobain. It caught Pearl Jam off balance. Stone Temple Pilots handled it a little too well, given how quickly they sold out. Given all that, Nine Inch Nails did not seem poised to weather the transition to rock stardom with ease. And yet, with The Downward Spiral, Reznor appeared collected, ambitious, smart and ready to rule. On paper, the whole industrial thing was too weird, dark and scary to ever dominate. But Reznor is a master craftsman with a flair for drama. Listening to songs like “March of the Pigs” and “Mr. Self Destruct” now, the tension of ugliness and prettiness is as riveting as it was in ‘94. One minute, the song is clattering along towards a disaster of percussion; the next, a beautiful tinkle of piano rescues the whole affair from the flames and sends it soaring over the destruction.

It’s what sets his “Hurt” apart from Cash’s. I’m sympathetic to the argument that Johnny did it better than Reznor, but hearing “Hurt” within the context of The Downward Spiral adds another layer of tension — you’re always wondering when the song is going to dissolve into something meaner or prettier (and it kind of does both). It’s that unbearable tension that makes The Downward Spiral such a thrilling listen. It inspired a whole generation of artists from Manson to Prodigy to Korn to Limp Bizkit to Linkin Park to Thursday. But some of those bands have ended up as shorthand for the worst kind of late ‘90s/early ‘00s buttrock, Nine Inch Nails’ legacy is secure. The tension he mastered during this era is still present in his work today. It’s hard to think of a better fit for the interior life of a guy like Carmy.

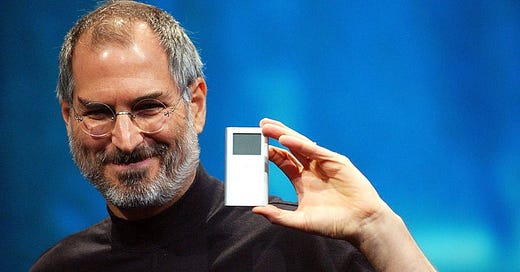

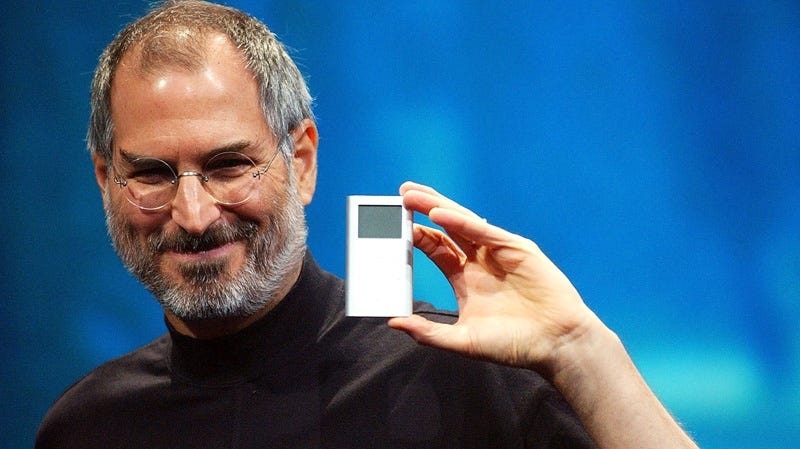

73: Steely Dan — Aja

I’m a big fan of Jay and the Americans’ “Come a Little Bit Closer,” a 1960s’ hit that sounds like it’s from the 50s and briefly made Jay and the Americans just about the only vocal act standing in the era of the Beatles and the Stones. Jay and the Americans’ band was made up of a rotating cast of musicians, and frontman Jay Black sent two of them packing mid-tour. He called them “the Manson and Starkweather of rock and roll.” Their names were Walt Becker and Don Fagen.

Jay’s opinion would end up being shared by most people who got to know these two. Walt and Don were prickly cynics who had very little interest in any part of the music industry save the music itself. They were New York music dorks whose fussy precision and detached cerebralism was out of place in the languid California rock scene. Cameron Crowe tried to interview them in 1977, and their disinterest in the conversation oozes from the page. But Fagen does drop one self aware quote: “These days, most pop critics are mainly interested in the amount of energy that is obvious on record: this primitive rock & roll energy. People who are mainly Rolling Stones fans and people who like punk rock, stuff like that …a lot of them aren’t interested at all in what we have to do.”

It took a while, but the world caught on to Steely Dan. Their legend was kept alive by a coterie of diehard fans and, later, sample-based artists who realized how useful their tight, sophisticated production could be. Then, for reasons I can’t quite ascertain, they got a huge Covid bump. For a while there, everyone was listening to Steely Dan, me included. There’s probably a lot of reasons for this and I don’t pretend to understand all of them, but there’s at least one I’m sure of: Steely Dan is amazing. I love Steely Dan. Steely Dan rocks.

It’s a highwire act of jazz, prog rock and R&B, laid down with divine precision. You know how in C.S. Lewis’ Till We Have Faces, Psyche is described as being so beautiful that you didn’t even notice it, because she just looked like how a person was supposed to look? That’s Steely Dan music. It’s not showy or immediately exciting. It’s almost easy listening. But the more you listen, the more you realize what a marvel it is. I like how Amanda Pratusich put it: “Aja is like driving down a treacherous, cliff-side road in the most luxurious car ever made: If you sink deep enough into that supple leather seat, it is possible to forget entirely about the twists and turns, the threat of looming destruction. It’s possible to forget about gravity entirely.”

Aja is one of the band’s better known albums, largely thanks to “Peg” and “Deacon Blues” but it’s still a strange ride, much more a jazz record than a pop one. The song structures are baffling in ways you don’t notice till you try to start singing along. Having left the ‘60s with a reputation for being esoteric oddballs, Becker and Fagen turned into the skid on ‘Aja.’ They were at home in the studio, where they’d spend all night writing and then all day with a revolving door of studio musicians, laboring over take after take until they got the exact sound they wanted. You can see how a process this exacting didn’t exactly mesh with the burgeoning punk scene, but the results speak for themselves. When Crowe asked Fagen if he was worried that Steely Dan’s sound wasn’t going to click with rock fans of the late ‘70s, he got a terse response: “I don’t care.”

It makes sense that hip-hop artists would carry the Steely Dan torch for the next generation. Rap is all about the sort of studio work that Fagen and Brecker excelled at, so MF Doom’s “Black Cow” sample on “Gas Drawls” or the “Peg” sample on De La Soul’s “Eye Know'' sound natural. I’m not the biggest Wiz Khalifa fan, but I love how he used “Josie” on “Old Chanel.”

Lyrically, Steely Dan were cryptic virtuosos, populating their songs with strange characters both real and imagined. Aja is a supposed real person*: the wife of a friend’s brother. Can you imagine writing an eight-minute jazz epic about the wife of a friend’s brother? Imagine being the friend. Imagine being the brother. Imagine being Aja herself! Your husband’s brother’s weirdo buddy wrote a whole song about you, with no less a legend than Wayne Shorter on the drums!

Deacon Blues is probably not a real person, although he might be at least a stand-in for Fagen and Brecker themselves — a wannabe bigtime musician whose brief life only looked glamorous from the outside. The lyrics here aren’t exactly straightforward — no Steely Dan lyrics are — but they still absolutely bang. “Learn to WORK / the SAX-a-PHONE” is just so much fun to sing out loud.

Steely Dan usually had the sense to be fun, which is really good, because the whole concept could have easily been stuffily pretentious. You can imagine Steely Dan copycats getting so caught up in the production that it sucks all the blood out of the songs. But there aren’t really any Steely Dan copycats. Their thing was too unique, too idiosyncratic for imitation. It’s probably for the best. Based on everything we know about the guys, we don’t need more than two of them in the world. But we’re lucky we got those two.

72: SZA — S.O.S

You couldn’t write “Barbara Ann” today. I mean, you could, but it wouldn’t make any sense. Who goes to a dance looking for romance? Who goes to a dance, period? We look for romance, when we bother to look at all, on the apps. The fundamental experiential building blocks of pop music involve a lot of external stimuli. “I’ve Just Seen a Face” — which is probably THE pop song — is all exterior. There’s a time and place. They want all the world to see. Today’s world is isolated, fragmented and interior. Whether or not this is a net gain for humanity is up for debate, but it’s not necessarily a bad thing for pop music. Just ask SZA.

SZA’s music is a soundtrack for the interior life. She is one of our chief chroniclers of mental landscape in the 21st century. Her songs are inner monologues, finely observed depictions not so much of what she’s going through, but how she’s processing what she’s going through. SZA’s eye is turned inward. Even when she’s writing songs about “you,” her real focus is on how she’s feeling about “you.” “How am I supposed to tell you I don’t wanna see you with anyone but me?”

This can make for a bracing listening experience. Kris Kristofferson once advised Joni Mitchell to “keep something for yourself” while songwriting, and if anyone is giving SZA the same advice, she’s not listening. Her lyrics are naked, intimate, contradictory, and frequently unflattering. This, of course, just means they’re real. And that’s where SZA achieves what is, I think, the greatest gift a songwriter can hope to give: assuring the listener that they are not the only ones who feel this way.

Solána Imani Rowe is a Jersey girl, raised in an interfaith home by a Muslim father and a Christian mom. She grew up in a safe, stable, loving household by parents who loved each other and loved her, which ought to be a great comfort to anyone who thinks traumatic childhoods are the only fields good art can be harvested from. She was drawn to her dad’s faith and wore a hijab until 9/11, when she was bullied out of it at school.

She was a gifted athlete and did gymnastics while studying marine biology at Delaware State and working at Sephora, only recording a few songs on the side as a hobby. She was helping a boyfriend hock t-shirts at a Kendrick Lamar show where she meant Punch Henderson, the owner of Top Dawg Entertainment. A friend gave him her CD. Henderson was impressed. Top Dawg was the new, red hot kid on the block at the time, but they hadn’t signed any women yet. SZA was the first.

“I’m this random girl from a small town and I annunciate all my words and I wear dirty Chucks and my hair is never combed; I don’t think they knew what to make of me,” she would later tell Billboard. “At first, I think they looked at me like an alien or something. ‘Your music is weird, you’re weird, but we like you.'” After Z and CTRL became monster hits, they liked her a lot more.

“Weird” isn’t quite the word I’d use for her music. “Eclectic” might be better, drawing on a ton of different influences for a global tour of music styles. Much of S.O.S stays in its Frank Ocean by way of Jill Scott register, but SZA also raps on “Smoking on My Ex Pack,” goes for sad girlie indie pop on “Ghost in the Machine,” bratty pop punk on “F2F” and even something approaching Mazzy Star meets Kacey Musgraves on “Nobody Gets Me.” There is something for everyone here, which can sometimes make for a disjointed listening experience. But SZA’s whipsmart production and idiosyncratic lyrical content tie the project together even when the disparate genres get wobbly.

She’s very funny, and mercifully willing to make herself the butt of the joke when she knows she’ being a little ridiculous. “I might kill my ex / Not the best idea,” she muses on the excellent “Kill Bill.” Or on “F2F” where she examines her feelings for both an ex-boyfriend and the rebound: “Get a rise out of watching you fall, get a kick out of missing your call / I hate me enough for the two of us.”

Music like this is great for a lot of reasons but like I alluded to earlier, I don’t think we can be grateful enough for the permission it gives. Hearing someone like SZA unspool her weirdest, darkest, saddest thoughts with this level of skill lets you know it’s okay. It’s okay to be both mad at your ex and to want him back. It’s okay to be both lonely and tired of being around people. It’s okay to feel ways that don’t make sense. The interior world is just as real as the exterior one, but it’s much more confusing and follows its own logic that very few of us really understand. Good thing we’ve got SZA to help us map it.

71: Kraftwerk — Trans-Europe Express

A person in the 70s would never have guessed that rock and roll’s time was growing short. The list of albums that define the decade — Zeppelin IV, London Calling, Exile on Main Street, Loaded, Who’s Next — sound like a genre of music only growing more dominant, more confident. Few suspected a new digital age was dawning that would reshape both the world and the way people respond to the world, socially, mentally and, yes, creatively. Almost nobody saw it coming. But Kraftwerk did. You could even argue they accelerated it.

Florian Schneider met Ralf Hütter in Düsseldorf in the 60s, and the two bonded over a shared love of experimental art and generally being weirdos. Schneider picked up a newfangled invention called a synthesizer in 1970 and started toying with it. They'd already taken a stab at a rock band that didn't go anywhere. Schneider was excited by the idea of synths and thought maybe this new sound could take their next project a little further. Hütter was interested.

Synths were a novelty through most of the early 70s. You can hear them in Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Stevie Wonder’s Innervisions, but they’re mostly color, a little spice to enhance the main ingredients. Schenider and Hütter were intrigued by synth on its own terms, not as a way to enhace the familiar but a way to take the familiar and make it strange.

That doesn’t necessarily sound like a recipe for international success and, at first, it wasn’t. The band’s first few albums are instrumental, experimental and exploratory. You can hear the technical expertise and Schneider’s knack for a pop hook, but it was all too odd to catch fire. However, Schneider had his finger on the pulse like few musicians before or since. Kraftwerk was paying attention to the burgeoning New Wave and punk scenes, and proved adept at finding ways to interpret those movements into their digital universe. By the time Kraftwerk released Autobahn and Radio-Activity, the band had figured out how to turn what they did into pop music. But with Trans-Europe Express, they turned pop music into what they did.

The result sounds icily inhuman, and Kraftwerk would spend their careers encouraging this robotic branding. But it was also mind-expanding, proof that electronic music could not only add to and expand the Beatles’ pop blueprint, but create a whole new kind of blueprint with its own possibilities. This was a very useful form of creative expression for a new generation of Germans anxious to divorce themselves from the past.

The rest of the world wasn’t sure what to make of it. Lester Bangs wasn’t a fan, and he made it clear in Creem. A 1975 Rolling Stone interview gave Kraftwerk a big platform, but the band was already leaning into a performatively mechanical persona that baffled the status quo even as it thrilled a small but loyal fandom. Schneider wasn’t necessarily the warmest guy, but he wasn’t nearly the android the press at the time made him out to be. He was happy to explain what Kraftwerk was doing to anyone who was honestly asking. “It’s not body emotion,” he told Bangs. “It’s mental emotion.”1

Mental emotion flows through Trans-Europe Express. The album is a sort of tribute to Europe’s transportation system, a celebration of modernity’s improvement of the European way of life. Kraftwerk knew that there was a growing disconnect between image and reality (“even the greatest stars discover themselves in the looking glass”) but they also knew that the trains of Europe are a modern miracle of connectivity.

They’re preaching to the choir. I love Europe’s train system. It’s one of the great wonders of the world, an absolutely unbeatable mode of travel. Give me a day of travel across Europe by train, a book and some AirPods, and I’m perfectly happy. Kraftwerk got that, but they also saw trains as a source of musical inspiration. The music on Trans-Europe Express is minimalistic, repetitive, mechanical and mesmerizing. It evokes a long train ride, the hypnotic chug of movement, the inconsistent stops, the sense of getting somewhere quickly but unhurriedly.

It was the 21st Century in 1977, the first real volley of a type of digital music that would come to define our listening habits, just as the digital world came to dominate our lives. It probably wouldn’t be fair to say that Kraftwerk made a value judgment on the digital revolution they anticipated, but they accepted it, embraced it and delivered on its promises. And in doing so, they pulled off the impossible trick of always and forever sounding like the future.

David Bowie and Iggy Pop were both huge fans, and Kraftwerk has often credited them with giving them the encouragement to keep going.