Apple Core: Neil Young, Eminem and Lana Del Rey

Our journey through Apple Music's Top 100 Albums of All Time continues.

Liz and I are listening to Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums of All Time. One album a day-ish, counting down to number one. We did this with Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 Albums of Al Time, and it took more than a year. This should only take a hundred days or so. I’ll be posting a few thoughts here as I listen. We’ll be dropping standout tracks from the listen on this Spotify playlist here.

Here’s parts one, two, three, four and five.

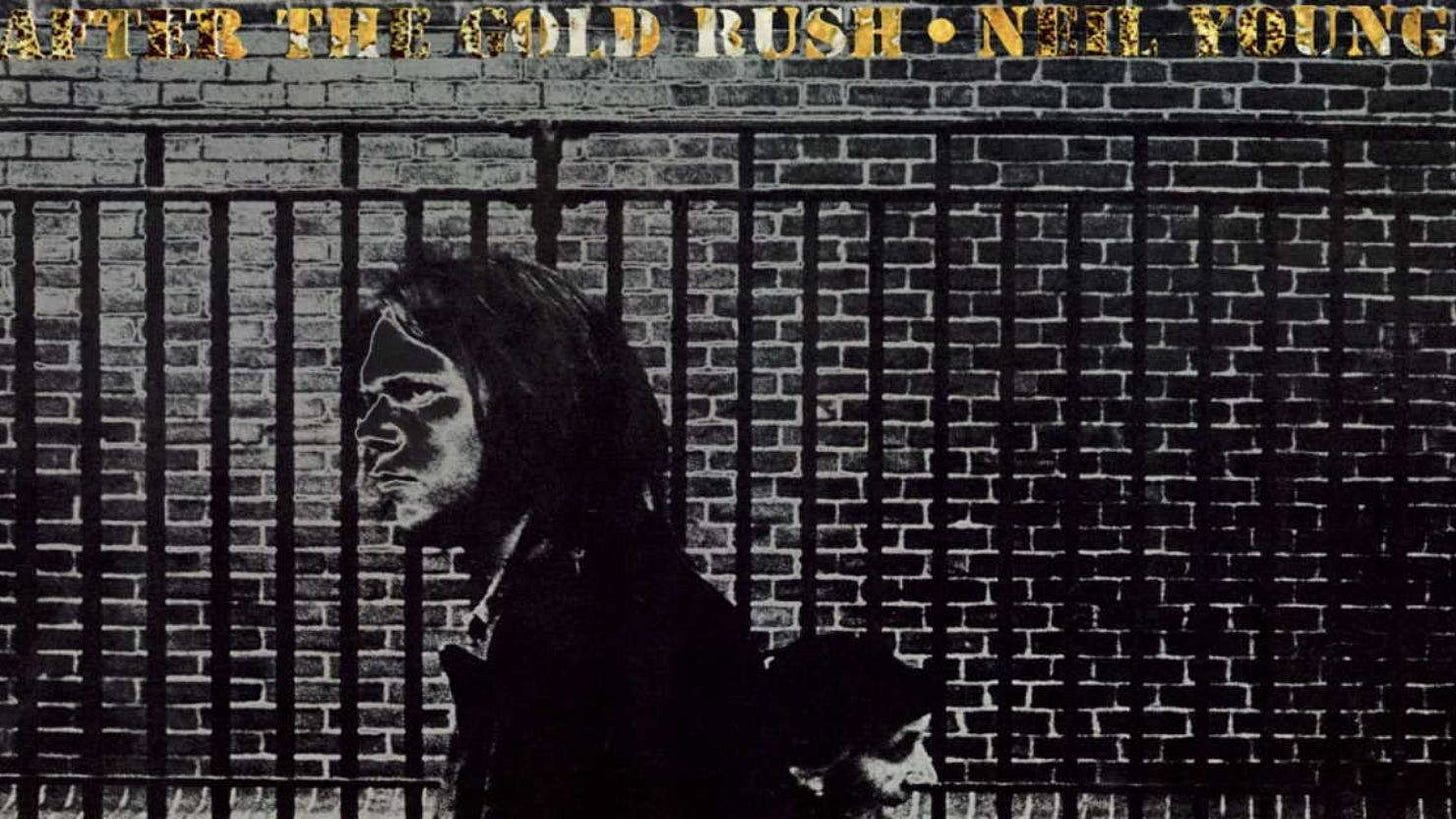

Day 81: Neil Young — After the Gold Rush

“Crosby, Still and Nash were fulfilled with what they were doing,” Neil Young recalls in his biography Shaky. “I guess they couldn’t understand why I wasn’t.”

That tension didn’t reach a breaking point, but Crosby, Stills and Nash were a little mystified by hotshot new recruit Young's insistence on pursuing a solo career right alongside their huge successful supergroup rocket ship. “We’ve got a good thing going here, Neil!”

But Young’s always been the sort of True Individualist that many of his hippie contemporaries imagined themselves to be. And following an interesting though not particularly memorable debut and the far more confident sophomore album, Young was ready to branch out. After the Gold Rush would not have the breakout power of Harvest or the career-shifting energy of Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, but a lot of Neil guys will tell you it’s his best.

Its origin story starts in Topanga, the California hippie community where Young was spending a lot of time. He’d recently joined Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, and his profile was exploding. He wanted to capitalize on this momentum, get his own Crazy Horse band back together and start recording some solo work. Just one problem. He couldn’t think of anything to write about.

That’s when his pal Dean Stockwell showed up. At the time, Stockwell was a former child star who’d since lapsed into only occasional TV work to cover his off-the-grid lifestyle1. He was working on a screenplay for a movie called After the Gold Rush that he thought had a real chance of getting made, and he wanted to know if Neil would be interested in recording a few songs for the soundtrack. Young said he’d take a look.

The script has not survived but the general recollection is that it’s some sort of Easy Rider meets Mad Max deal with a few hints of Fern Gully and Star Wars, a postapocalyptic parable about a coming ecological disaster. Stockton later recalled that it was "a Jungian self-discovery of the gnosis. It involved the Kabala; it involved a lot of arcane stuff." Young himself remembers it as “a little off the wall.”

Off the wall or not, it jolted Young out of his writer’s block. The movie, for better or worse, never got made. But it lives on music form, and you can still hear whispers of what might have been in the title track’s narrative of spaceships carrying mankind off to new planets after this one goes tits up.

But it’s not all sci-fi Jungian self-discovery of the gnosis. Songs like "Southern Man" and "When You Dance I Can Really Love" showcase Young and Crazy Horse’s gift for kushed out jam sessions with an intensity that catches you off guard. His fans already knew about that. But “Birds,” that title track and the famous “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” put Young’s greatest gift on a pedestal: The man simply knows how to write a melody.

Even if you find his voice a little grating and precious (as I do), you cannot deny his gift for a simple chord progression that can take your breath away. There are moments on “Only Love Can Break Your Heart” — a song he wrote to comfort Graham Nash in the wake of his breakup with Joni Mitchell — so obvious and beautiful you can’t believe that melody had always been available in the world for anyone to use until Young came along and plucked it out of the ground.

The atomic perfection of these melodies contrasts against Young’s famously imperfect style of playing. He asked teen guitarist wunderkind Nils Lofgren to play the piano for a track and Nils admitted he didn’t know how. “Great,” Young said. “That’s the kind of pianist I’m looking for.” Your tolerance for Young’s intuitive mess probably depends on what you’re looking for out of music.

But as it turns out, After the Gold Rush was fortuitously titled, even if the movie never materialized. The phrase captures the dawning of sense of doom that hovered over California and the U.S. as a whole as the liberated optimism of the late 60s ran up against the ugly realities of the 70s: Nixon, Nam, Manson, and a climate disaster that continues apace to this day. His ramshackle, loose knit playing style suited the warbly anxiety of a nation on edge. Creative fulfillment is a complicated beast in the face of such multifarious crises. Is it any wonder Young felt the need to branch out?

80: Eminem — The Marshall Mathers LP

I was not prepared for Detroit. No number of stories about its crumbling ruins and widescale abandonment could have prepared me for the visceral shock of driving through a downtown that looked lost to time. Skyscrapers being reclaimed by nature. Whole city blocks inhabited by nothing but the wind. A blinking digital clock of a city.

But there is something about the failure of traditional markets that does inspire a sort of artistic fervor bordering on desperation. My friend Garret2 has pretty much dedicated his life to empowering Detroit artists to revitalize their city, and he’d be the first to tell you that just because capitalism failed doesn’t mean the city is dead. Detroit may not be leading the world in automotive output anymore, but it’s still giving us wonderful artists. It gave us MC5. It gave us the White Stripes. And most improbably of all, it gave us Eminem.

A thousand corporate executives in a thousand years could not have created Eminem. The highest paid industry strategists in the world would have laughed at the very idea of him. At the turn of the millennium, when the traditional music business found itself at the mercy of Napster pirates on the turbulent waves of a dawning internet age the industry refused to understand, a scrawny white rapper came through and held them afloat almost all by his lonesome.

His name was Marshall Bruce Mathers. He was born in St. Louis, but ended up in a squalid Detroit apartment with his mom after his dad split. It wasn’t a great childhood. He was broke, annoying and mercilessly bullied by bigger kids. One time he got beat up so bad his mom sued the school district. School, in general, didn’t work out great for him. He repeated the ninth grade three times. At some point in there, his mom took in a teen runaway by the name of Kim.

Em dropped out of school and started picking up odd jobs. His Uncle Ronnie introduced him rap before dying by suicide, and young Eminem devoted himself to the study of hip-hop. He started testing his mettle in rap battles like the ones you saw in 8 Mile, but he didn’t have much success. The general consensus from Em’s early days is that he had raw talent to spare, but it was unfocused and undisciplined. Plus, he was a white kid in an overwhelmingly Black environment. This would soon be a key element to his global domination, but it was a liability to his fledgling career. His debut mixtape went absolutely nowhere. He was washing dishes for minimum wage. By this point, Kim had given birth to Em’s daughter, Hailie3. He was in a desperate place.

Out of options and recovering from his own failed suicide attempt, Em created a cartoon persona he called Slim Shady. The real Eminem was depressed, ornery and angry. Slim Shady was a gleefully transgressive little goblin. As Slim, Marshall was able to do somethin that had eluded him so far: get a little music career going. In 1997, he came in second in an LA rap battle, missing out on the $500 prize money but getting his mixtape into the hands of Jimmy Iovine, who passed it along to Dr. Dre. When Dre heard the tape, he only had three words: “Find him. Now.”

White rappers were a joke in 1999. Beastie Boys had been godfathered into a respectable stratosphere, but Vanilla Ice and Marky Mark were already saddled with all the cringe they’re still carrying now. Labels were not looking for a white rapper with mainstream pop appeal. But Eminem was simply undeniable. He could really rap. He was savage, creative and very funny. His openness about the struggle to make a buck hit home, and his vicious tirades against authority figures, women and (most of all) himself struck a nerve. As Tom Breihan writes at Stereogum: “Suburban white kids had been buying rap records for years, and now Dr. Dre, the man who’d discovered how to sell street-rap in blockbuster numbers, was introducing these kids to a white guy who could rap as well as just about anyone. It clicked.” On the strength of lead single “My Name Is,” Em’s 'Slim Shady LP' went triple platinum.

The follow-up, this album, went way more than triple platinum. It was a phenomenon. In 2000, you just could not go outside without hearing “The Real Slim Shady” or “The Way I Am” coming out of a speaker somewhere. The latter features some of Em’s most dexterous wordplay, juggling multi-layered rhymes that land like the hip-hop equivalent of a triple axel. How on earth did he come up with that stuff?

The numbers got a nice boost from an Eminem-centric moral panic. Slim had dialed the violence in his lyrics up to eleven, bathing his songs in cartoonish levels of blood that terrified media pundits and politicians who screamed for his head on a plate. Look. I’m not going to spend a lot of time in these essays talking about the moral content of lyrics, because I think it’s one of the cheapest ways to talk about morality. It’s hard to take elected officials’ hyperventilating about violent lyrics seriously when they’re also bending over backwards to block any measure aimed at curbing gun violence. It’s hard to take their concern about misogyny and homophobia seriously when they’re passing laws that make life for women and queer people materially worse. They made Eminem a scapegoat for their own failures, and he was right to be mad at them for it. All that said, the misogyny and homophobia in Eminem’s lyrics is real and it’s shocking.

For the most part, Em responded to criticism of his lyrics by doubling down on it4 — a proto-social media troll. But this album also features “Stan,” probably his most thematically fascinating track, a real attempt at reckoning with the impact he’s having on his audience and, somehow, the song that’s ended up making a contribution to Webster’s Dictionary. Em has since said that he wrote “Stan” — a fictional correspondence between himself and an increasingly crazed fan over a spidery beat and a Dido sample — as a way to “make the critics who were saying things about me feel stupid.”

I’m not sure it accomplished its mission there. But Eminem eventually rapped his way into the Great American Songbook — thanks in no small part to 8 Mile and “Lose Yourself,” which lionized his genuinely harrowing backstory and regulated the cartoon troll to a footnote in his Rocky-like hero’s journey. In 2000, pop music was all fake plastic candy and simpering teen pop. Eminem was counter-programming. He triumphed against all odds. Detroit is still a long way from the highs it achieved at the peak of the industrial revolution. But when it was near its lowest, it gave us an artist who revolutionized a whole different industry. And he did it all with mom’s spaghetti on his sweater.

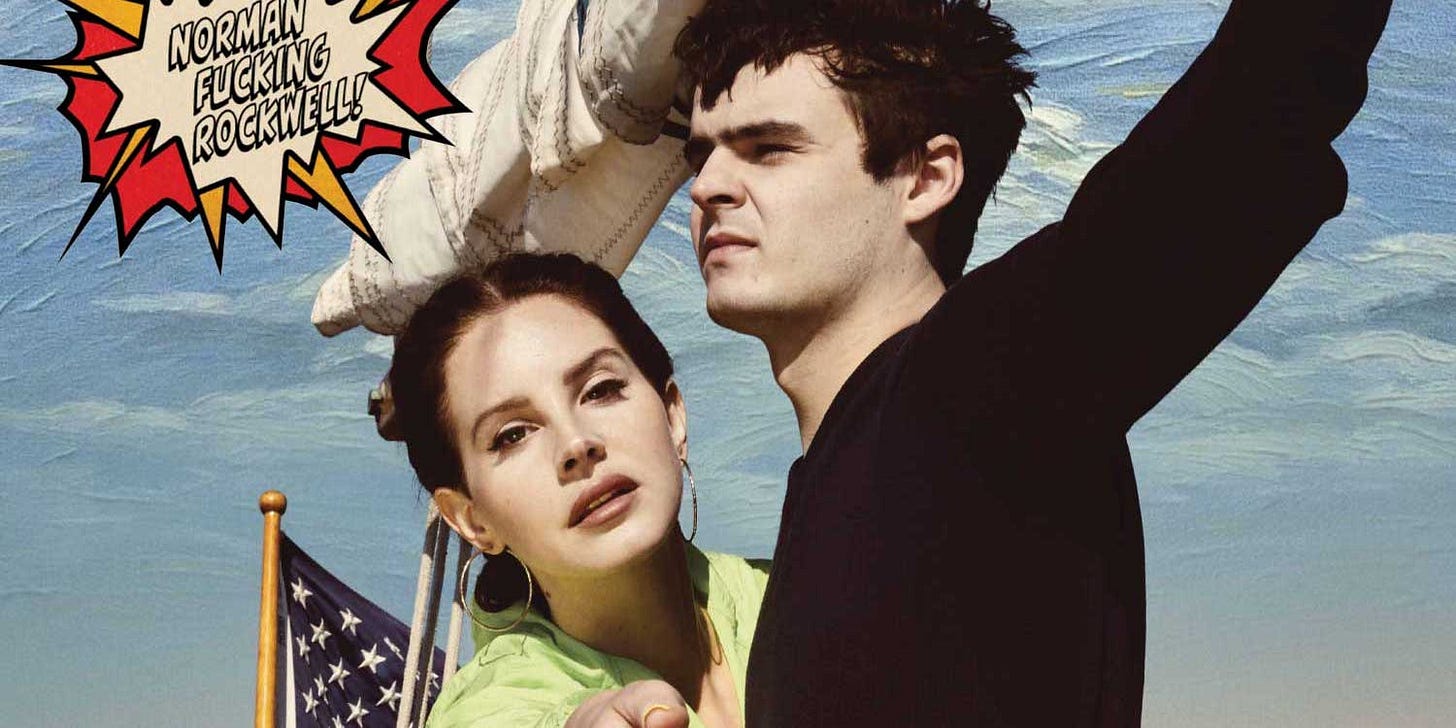

79: Lana Del Rey — Norman Fucking Rockwell!

“We used to go to the California coast and stay there secretly in a cottage on a beach far away from all the prying eyes. We’d spend much of our time on the beach, sitting there or fooling around just like college kids. We would talk about ourselves and our problems, about the movies and acting, about life and life after death... We had a complete understanding of each other. Sometimes, we would just drive along and stop at a hamburger stand for a meal or go to a drive-in movie. It was all so innocent and so emphatic.”

This is the Italian actress Anna Maria Pierangeli talking about her brief, tragic affair with James Dean. Paul Newman introduced the two while he was filming The Silver Chalice and it was, by all accounts, love at first sight. He said she looked like Cinderella. He even called her Annarella. They dodged paparazzi and sneaked away to the California coast. She would later say that: “sometimes on the beach we loved each other so much we just wanted to walk together into the sea holding hands because we knew then that we would always be together.” Seven months after they met, Dean asked Anna Maria to marry him. She said yes.

It was not to be. Anna Maria’s mother hated Dean. She forbade her good Christian daughter to marry a rough-and-tumble skeptic, and ordered her to not only renege on the proposal but to never see him again. Fate obliged on Dean’s behalf. He was killed in a car wreck just a few months later. There was an unsent letter to Anna Maria in the glove compartment. Fifteen years later, Anna Maria overdosed in Beverly Hills. Fifteen years after that, Lana Del Rey was born in Manhattan.

Lana had nothing to do with any of that, but it has everything to do with her. Anna Maria’s beautiful recollection of her time with James Dean hums with the bittersweet euphoria of a Lana song, shot through with themes and iconography you’ll find in the best of them: escaping the colossal shadow of an American myth in the making for long weekends of cheap burgers, old movies, amazing sex and all-night discussions of death and whatever comes next; doomed romance, doomed lives, the way even an attempt to escape the myth became part of the myth itself. This is the world Lana inhabits and dissects. Norman fucking Rockwell, baby.

Amateur Internet sleuths really thought they’d done something when they discovered that Lana Del Rey had been born Lizzy Grant, a Fordham grad living in a New Jersey trailer park. They held this up as proof that Lana Del Rey was fake. They had no idea how right they were, how many light years behind her they were. Fakeness is Lana’s playground. It’s her operating room. It’s the canvas upon which she paints and the window she looks through to see America for what it is. She understands that America is an inauthentic place, and you can only understand the real thing through that inauthenticity. You’ve gotta come at it sideways, walking into it backwards with a martini in one hand and a Bible in the other. So she fully inhabits our fakest myths, possessed by the spirits of Jackie Kennedy, Joan Didion, Jessica Rabbit and Jefferson Airplane, even as she splits them open, getting at the truths in their guts.

Those internet sleuths didn’t get that and neither, at first, did reviewers. Born to Die made Lana Del Rey an overnight viral sensation but whiffed with critics for a lot of reasons that look awfully sexist in hindsight. The AV Club tried to take Lana to task for embodying an “outmoded imagining of the ultimate male fantasy” who “exists only to titillate.” Stereogum said her lyrics sounded like “a drunk chick at the bar trying to convince someone to come home with her.” They didn’t get it.

Critics had gotten a little wiser by the time Norman Fucking Rockwell came out,5 but Lana had also added experience to her toolbox. She’d always understood that the American Dream was a rapidly crumbling artifice. On NFR, she groked her place in the grand tragedy. “The culture is lit and I had a ball,” she sings. “If this is it, I’m signing off.”

Every song on here sounds like the last song. Not just the last song on the album, but the last song ever — a swoony serenade for the end of the world, something for us to fall asleep to as the glacial melt laps over the highest point on the Hollywood sign. Nero fiddled while Rome burned. Lana’s lighting joints on the smolder. The country may be going down in flames but, hey, it’s home.

For Lana, the most seductive part of the American Dream is not the stable job, the white picket fence or the kids. It’s the man. Lana has always longed for a man to fix, and here she elevates this urge to messianic stratospheres: “Maybe I could save you from your sins.” She knows it’s a hollow dream (“why wait for the best when I could have you?”) and she knows she’s barely fooling herself (“if he’s a serial killer then what’s the worst that could happen to a girl who’s already hurt?”) but she also knows this is what the American Dream does: lures you into numb acceptance of its most corroded mutations.

It all sounds gorgeous. Jack Antonof handled the production and whatever criticisms people have of his recent work, he was absolutely in his bag here. Everything is dreamy, warm and glamorous, coaxing you into its lush cabaret lullaby. The first act of “Venice Bitch”’s ten minute runtime is a lovely, fluttering portrait of an almost-happy romance. “You’re beautiful and I’m insane,” Lana sings. “We’re American-made.” But as the song continues, it slips into her insanity. The two dimensional cutouts start toppling over to the tune of a coked out guitar solo and the clarity of her voice dissolves into a feverish warble: “We’re getting high now because we’re older.” “The Next Best American Record” is a midnight praise chorus about Lana and her man skinny dipping in Topanga while working on their masterpiece. “You made me feel like there’s something that I never knew I wanted,” she sings over a tick-tock beat before breaking into “we play the Eagles down in Malibu” in a melody so achingly beautiful I cannot believe a band as boring as the Eagles inspired it.

Like I said, any song could work as the ending song, but Lana chose the right one. “Hope is a dangerous thing for a girl like me to have - but I have it” is as simple and direct as she’s ever been. Backed by nothing but a piano, she clings on for dear life. “I’ve been tearing around in my fucking nightgown, like a goddamn near sociopath.” She mourns “church basement romances.” She’s writing in “blood on the walls” because her pen’s out of ink. She misses her old man: “Calling from beyond the grave, I just wanna say ‘Hi, Dad.’” Here all the disparate women she’s been exhuming — Sylvia Plath, Daisy Buchanan, Marilyn Monroe, Pamela Des Barres, Sharon Tate and Anna Maria Pierangeli herself — unite into a single, unique whole: herself. And in the middle of it all, the chorus floats into clarity, a beam of light through the clouds. “Hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have,” and finally, mercifully, in her highest, quietest register: “but I have it, I have it, I have it.”

A few years later, he’d land a plumb role in Blue Velvet and then star in Paris, Texas, one of the best movies ever. This led to a very solid career right up until his death in 2021.

Please check out Assemble Sound, support their artists and buy their merch so they can keep doing what they do.

In 2013, Eminem released "Headlights," a song full of apologies to his mother for all the mean things he rapped about her. It features a chorus from Fun's Nate Ruess. The song is bad but it's the thought that counts. In 2017, he apologized to Kim on "Bad Husband." That song is even worse, but I hope it brought some peace to those most directly in need of it.

Relatedly: more women had kicked down the door to those jobs, many of whom had come up through the Tumblr ecosystem that idolized Lana from day one

Also! The entire paragraph and observation about every song sounding like the last song — damn. That’s perfect. (Also re-listened to the “play the Eagles down in Malibu” part and my goosebumps are profound.)

Dude, I’ve been loving this series (!). The Eminem piece was great, but the Lana one made me fall on the floor. This bit: “She understands that America is an inauthentic place, and you can only understand the real thing through that inauthenticity. You’ve gotta come at it sideways, walking into it backwards with a martini in one hand and a Bible in the other” — tremendous.