Apple Core: Kacey Musgraves, Patti Smith, Snoop Dogg and 50 Cent

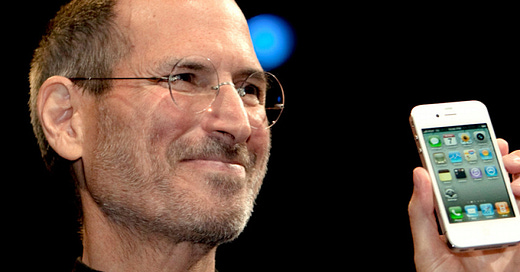

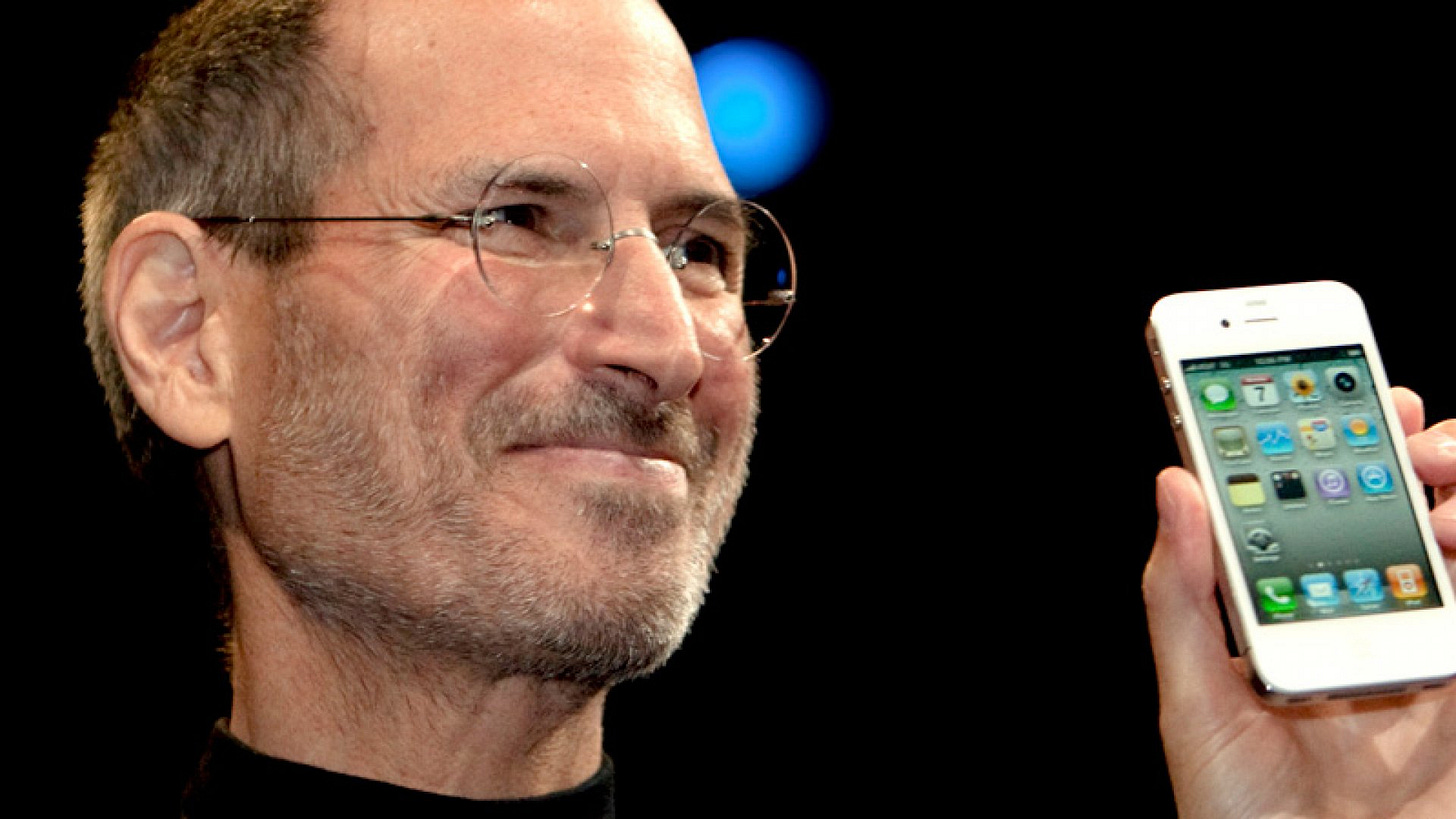

Our journey through Apple Music's Top 100 Albums of All Time continues.

Liz and I are listening to Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums of All Time. One album a day-ish, counting down to number one. We did this with Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 Albums of Al Time, and it took more than a year. This should only take a hundred days or so. I’ll be posting a few thoughts here as I listen. We’ll be dropping standout tracks from the listen on this Spotify playlist here. Here’s parts one, two, three and four.

Day 85: Kacey Musgraves — Golden Hour

Last December, I went to a big Christmas party at a friend’s house and Kacey Musgraves was there. It wasn’t super surprising, since there were a lot of music industry types present, but you still saw people whispering and stuff when she showed up. Later on, a guy sat down at the piano and started plinking out Christmas carols. I don't think he planned on it or anything. He just felt like playing Jingle Bells. A few minutes later, Kacey sat down next to him and started singing along and, before you could say “deck the halls,” the whole party gathered around and listened to Kacey Musgraves treat us to about an hour’s worth of Christmas songs.

I tell you that story for two reasons. First, because it’s one of those cool, impromptu Nashville things that used to happen a lot more, and I like sharing it. Second, because it gets at Kacey’s whole thing: She’s your relatable buddy, singing just outside your bedroom window, sharing her observations as they come to her. Golden Hour captured her at the peak of this power, with Musgraves’ warm, summery melodies opening up as organically and unhurriedly as a flower blossom, gently unspooling her thoughts about life, love and …well, mostly love.

Musgraves came up just left of the country music scene’s center, garnering a lot of attention without racking up a lot of hits. She was a Texas girl, and she learned to play Texas country while also learning some tough lessons about expectations for women in the country music scene. Country has always and probably will always be a hostile space for women artists. No matter how many Dollys, Lorettas, Rebas, Shanias and Taylors keep the industry afloat, Nashville’s powers-that-be will continue to place their hopes on the Morgan Wallens. Musgraves isn’t an idiot, and knew country music wasn’t going to be an easy road, so she leaned into her outsider status early. Songs about getting high and kissing girls burnished these Millennial neo-country bonafides, but she did it all in rhinestones and cowboy boots, so the scene couldn’t ignore her entirely.

But it’d be a mistake to call her a “rebel” or any of the brands typically associated with outlaw country types. Musgraves doesn’t kick back against the hard rules of country music so much as she just ignores them. Golden Hour has too much twang and grit to be mistaken for anything other than a country album — just like her voice itself would never be mistaken for anything other than a country singer’s — but the songs are too playfully experimental to get grouped in with Carrie Underwood.

There’s “High Horse,” the dizzy barn burner that smacks ever so slightly of disco. Or “Oh, What a World,” where a choir of banjos and steel guitars all sigh into a heavenly cloud that sounds like Glen Campbell covering Moon Safari-era Air. You didn't know butterflies' wings made a sound, but the gentle keys on “Butterflies" somehow does evoke that kaleidoscope flap. And I really do think my favorite might be "Space Cowboy," where Kacey comes closest to a Faith Hill country banger, but the hints of vocoder and reverb keep things just slightly weird.

It’s all radical, and not just by pop country standards, but the melodies are so exquisite you almost don’t notice how daring it is.

Musgraves has said she wrote the album during a big LSD phase, and Golden Hour does approach something I’d call “psychedelic country” Not in the jammy Grateful Dead sense, but because of the pervasive, blissed out calm that hangs over even the album’s uptempo stuff. A lot of the lyrics have a “shower thoughts” quality to them (“In Tennessee, the sun’s going down / But in Beijing they’re headed off to work”) but she delivers them all the wide eyed wonder of the crazy in love who can’t help but tell her boyfriend every thought that comes to her as it comes.

This is Musgraves’ gift. At her best, she knows how to make her loudest ideas sound conversational and her flashiest inspirations seem obvious. All of her genre experimentation and boundary pushing happens so organically you don’t even realize what a ride you’re being taken on. She just shows up at the party and starts playing.

Day 84: Snoop Dogg — Doggystyle

Last year, Martha Stewart briefly made headlines as the oldest model to ever appear in Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition. I don’t really know how we’re supposed to feel about the Sports Illustrated swimsuit edition in 2024 but in my opinion, if you’re 81 years old and you want to pose for a magazine in your swimsuit then, by all means, knock yourself out. I thought she looked great, not that my opinion really matters. Anyway, she was doing a video interview about the experience when her phone buzzed and she picked it up. “Oh, it’s Snoop!” she said, her eyes lighting up as she opened the text, which she then read out loud. It said: “Love you. Be right up.”

This is the Snoop Dogg most of us know now: a charming, non-threatening cultural icon. A friend to little old ladies, semi-regular White House attendee and frequent guest of fresh faced pop stars on bubbly pop tracks. You see Snoop almost anywhere and you’re likely to react just like Martha Stewart did: “Oh, it’s Snoop!”

On the surface, it seems like a pretty unlikely career trajectory for Calvin Broadus Jr. But then, when you interview people who knew Snoop back in the day, none of them seem surprised. Everyone knew he was destined for big things. Those big things didn’t exactly start with Doggystyle, but it was the album that cemented him as a major force in hip-hop — a new, inventive and clever emcee determined to make his mark on the industry with witty lyricism, fresh production and endless reams of cool.

Calvin Broadus grew up in Long Beach. His dad left the family when he was just a baby. His mom called him Snoopy because she thought he looked like Snoopy. The name stuck. Snoop had plenty of early run-ins with the law, but he was a bright student and a welcome presence at his church, where he played piano (he returned to these roots in 2018 with a gospel album). In high school, Snoop started rapping with his cousin Nate Dogg and their friend Warren G. A tape of their rap made its way to a guy by the name of Dr. Dre.

Dre was already a titan of West Coast hip-hop thanks to NWA. But he was starting to establish himself as a producer and incubator of young talent, which is now arguably a bigger part of his legacy than even Straight Outta Compton. Dre knew a future star when he heard one, and he brought Snoop down to his fledgling Death Row Records to lay down some verses for his upcoming debut as a solo artist. The Chronic was an instant classic and Snoop is all over it. People wanted more. He gave them Doggystyle.

California G-funk was ascendant in the early 90s, and Snoop wisely soaked his debut in easy, hypnotic beats, farty bass and gooey synths. The sound is a terrific accompaniment to Snoop’s laid back flow, which is a vibe all to itself and set Snoop apart from his West Coast colleagues. Dre had more authority, Cube had more menace and Tupac was Tupac, but Snoop had something none of them did: He was chill.

Chill oozes from Doggystyle. It opens with Snoop and his lady in the tub and only rarely shifts into a higher gear from there. Even on party anthems like “Who Am I (What’s My Name)?” and “Gin and Juice,” you can imagine him rapping the whole thing with his feet kicked up on the sofa. I don’t think Snoop was the best or most versatile rapper to come out of the early West Coast scene, but he’s probably the only one who could credibly deliver “bow wow wow, yippee yo yippee yay” and make it sound cool. Even when the gear does get a little darker — as on the haunting, paranoid “Murder Was the Case” — Snoop still maintains an even flow. Like NWA and Pac, Snoop was unsparing in his depictions of crime in his community, but he was strict about keeping his delivery chill.

But don’t mistake Snoop’s chill for harmlessness. By the time Doggystyle released, Snoop was already facing a first degree murder charge. He was eventually acquitted (it turned out his bodyguard had actually pulled the trigger) but the experience shook him up. He had a son to think about, and started pivoting his career towards becoming Snoop Dogg as we think of him today. None of his subsequent albums have made the impact Doggystyle did (although his Pharrell collab “Drop It Like It’s Hot” came close) but his legacy is bigger than any one album. He’s one of the most enduring characters in hip-hop. He’s friends with Obama. He’s friends with Martha Stewart! Oh, it's Snoop!

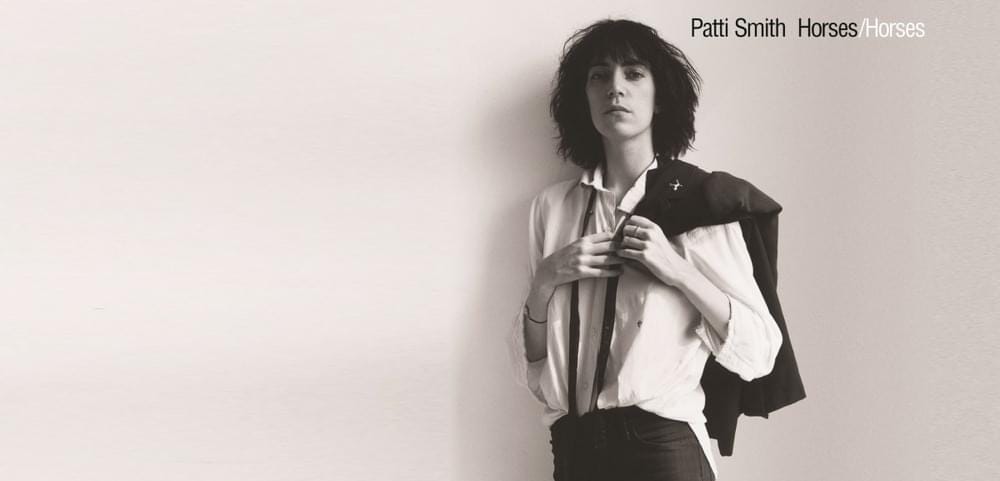

Day 83: Patti Smith — Horses

“You’re not Dylan Thomas, I’m not Patti Smith,” sings a certain someone who I’m sure will turn up on the list sooner or later. I don’t disagree with Taylor here. I’m not a Taylor Swift hater. She’s very frequently good at what she does. But Patti Smith opened her debut with “Jesus died for someone’s sins, but not mine.” Can you imagine Taylor Swift writing something like that?

It’s a hell of an opening line. It’s shocking. It’s blasphemous. It’s sad. It’s cool. It’s wrong, which is probably the point. It punches you in the face so hard that you lean in again to see what else this song has got. And in the case of Horses, what it has is eight more tracks of lyrics that hit with equal or greater force. It was enough force to start a whole new music scene, a whole new kind of music.

Patti Smith was always, first and foremost, a writer. She grew up obsessing over Arthur Rimbaud and the Beat poets, but she also loved the Doors, the Stones, James Brown and, above all, Bob Dylan. She chased their spark to New York, where she got work writing for Rolling Stone Magazine and Creem. She also fell in with her heroes’ spiritual descendants — guys like Lou Reed, Blue Öyster Cult and, of course, Robert Mapplethorpe. She did poetry readings in between paid writing gigs and at some point asked a record store clerk/writer named Lenny Kaye to play guitar while she read. Their partnership solidified, they moved into the Chelsea Hotel, started cutting singles and, eventually, an album produced by the Velvet Underground’s John Cale.

All of this is recounted in her 2010 memoir Just Kids, which has become almost as much of a touchstone as Horses itself. Whether music, criticism, poetry or music, this woman can write. Just Kids is a beautiful book that I loved reading, but nothing can really touch the thrill of Horses. Her debut courses with the ramshackle punk rock energy of youth; an urgent comet of essential, furious light. Listening to Horses now, it’s easy to see how this album almost single-handedly transformed the CBGB from just another New York dive bar into the North Star of the burgeoning punk scene. The guitar snarls are gripping and Cale’s production has pretty much defined punk ever since, but at the center of it all is Patti herself, twisting her voice into leaping, crawling, sprinting, cartwheeling spider of a thing, unpretty, unbelievable and unforgettable. “It was as if someone had spread butter on all the fine points of the stars,” she sings on the beautiful, terrifying Birdland. “Cause when he looked up, they started to slip.” Good grief. That’s how you do it.

Horses did well for such a bracing, deliberately off putting album, becoming a vital addition to the record collection of any self respecting music fan (especially punk rock girls, for whom Smith became what Stevie Nicks is to the folk rock girls). Smith’s later work would do even better numbers — especially her famous Springsteen collab “Because the Night” — but she was never better than Horses. This album captured her at her rawest and most interior. She sounds utterly possessed on “Free Money,” but if you peer through the storm you don’t see any outside forces or diabolical entities. Just Smith, writhing, leaping, screaming and writing, always writing, always finding the perfect words for the inexpressible.

When Tortured Poets Department came out with that aforementioned Taylor lyric, Smith wrote a thank-you note: “I was moved to be mentioned in the company of the great Welsh poet Dylan Thomas. Thank you, Taylor.” That’s how you do it.

Day 82: 50 Cent — Get Rich or Die Tryin’

For a few weeks there in 2003, one fact united America: 50 Cent had been shot nine times. 50 Cent, the rapper. He’d been shot. Not, like, recently. He’d been shot before. Nine times. It was his origin story, his radioactive spider. Other rappers may talk a big game about keep it real, but 50 Cent had actually been shot. Nine times! It was all anyone knew about 50 Cent. Well, that and the beat to “In the Club.”

“In the Club” was inescapable, an era-defining monster jam, the sort of thing that can reliably turn the mood up at any party. I was at a wedding last weekend and trust me, “In the Club” is still changing lives on the dance floor. It’s an interesting hip-hop classic. Lyrically, it’s all bottles of bub and partying like it’s your birthday. Sonically, it’s a ‘90s action movie — exploding helicopters and slo-mo shootouts. The instrumental track had been written a few years earlier by Dr. Dre and his regular collaborator Mike Elizondo, and had been floating around a few studios. Nobody could figure out what to do with it. Nobody except 50, who grabbed a pen and paper as soon as he heard it and had the lyrics ready to go inside an hour. Dre was apparently surprised that 50 wanted to use such a menacing track to rap about having a good time out with your boys, but that tension is what makes “In the Club” click. It gives partying with your friends the dark energy of a villainous plot to steal the Empire State Building. This tension was key to 50 Cent’s whole entire career, and it turned him into a titan.

That little piece of trivia about 50 getting shot nine times is true, but it barely hints at the violence and tragedy of 50’s life. Curtis Jackson grew up in Queens, raised by a mom who dealt drugs for notorious New York kingpin Lorenzo “Fat Cat” Nichols. He was eight years old when his mother was poisoned by a rival, and he got shuffled off to his grandparents’ home where he got swept up in dealing crack and heroin. He started street rapping in between jail stints, and a tape made its way to Run DMC’s DJ Jam Master Jay. Jay liked what he heard and took 50 under his wing, mentoring him on song structure. 50 got signed to a small Columbia imprint, where he released “How to Rob,” which ended up on the soundtrack for the 1999 Omar Epps vehicle In Too Deep. “How to Rob” — a darkly funny track about 50 would go about sticking up various high profile rappers and R&B singers of the day — was a hit and made 50 an instantly infamous figure in the music scene. Maybe a little too infamous.

In 2000, 50 was walking out of his home when he got hit with a hail of gunfire. He survived, but not without scars. You can still see the dimple on his cheek left by a bullet. You can hear the slight, almost Southern draw in his voice left by a bullet fragment in his tongue. The shooting cost him his recording contract — his label didn’t think he’d be around long enough to make it worth the investment. 50 limped out of the hospital weeks later with little to his name except a cane and a crazy story. And that story would turn him into a star.

With few business prospects, 50 started releasing mixtapes. He recorded them in Toronto, since no New York studio wanted him anywhere near the building, but they started getting passed all over the U.S. and became word-of-mouth hits. Eminem got his hands on a copy and loved it. He flew 50 out to Los Angeles and introduced him to Dr. Dre. Next thing 50 knew, he was rapping on the soundtrack for 8 Mile.

Dre handled production on 50’s debut album Get Rich or Die Tryin’, and caught him near the peak of his mid-career reinvention. He was positioning himself as the sonic equivalent of Michael Bay — both technically proficient and bursting with over-the-top bombast. It suited 50’s malevolent style. He had already developed a reputation for being a hip-hop supervillain. Get Rich or Die Tryin’ found him turning into the skid. He had a body like Captain America, the blessing of Dr. Dre and Eminem, and a knack for unstoppable hits that sent Get Rich or Die Tryin’ to quadruple platinum status.

Get Rich or Die Tryin’ courses with disdain. 50 spends a lot of time going after his haters with a mix of amusement and revulsion. He does a lot of rapping about crime, but he made crime sound like a good time. He deployed the same hustle towards chasing his pop instincts as he had on the street. It was a potent combo. A gunman had left him for dead. Instead, he created a legend.