Applecore: Arctic Monkeys, Oasis, D'Angelo and the Cure

Our journey through Apple Music's Top 100 Albums of All Time continues.

Before I get to the good stuff, Religion News published my article about “Christians for Kamala” or, more accurately, why I’m hesitant to call myself a “Christian for Kamala,” even though I am technically a Christian who is voting for Harris. You can read it here. Many thanks to my editors for working so hard to turn my scribbling into something legible.

Let’s listen to some music!

Liz and I are listening to Apple Music’s Top 100 Albums of All Time. One album a day-ish, counting down to number one. We did this with Rolling Stone Magazine’s top 500 Albums of All Time, and it took more than a year. This should only take a hundred days or so. I’ll be posting a few thoughts here as I listen. We’ll be dropping standout tracks from the listen on this Spotify playlist here.

Here’s parts one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, ten and eleven.

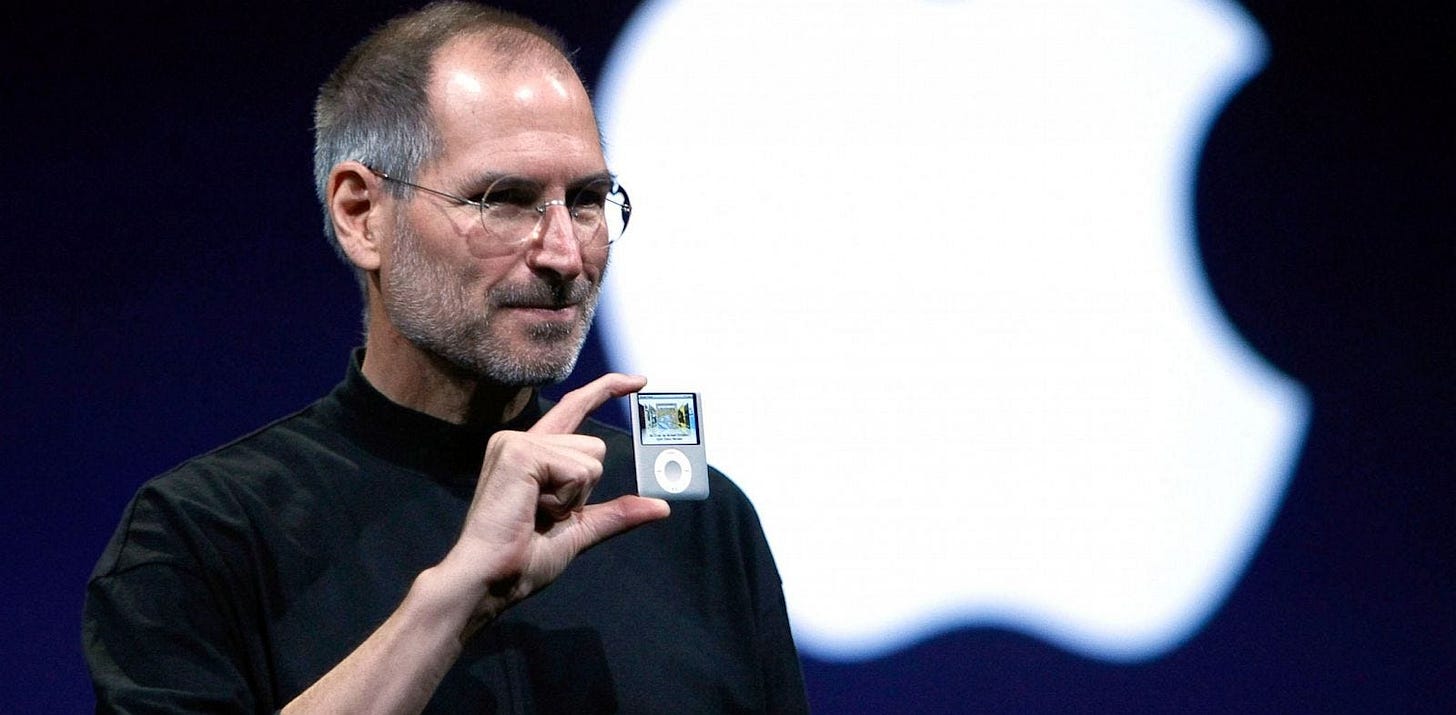

Day 59: Arctic Monkeys — AM

Frontman Alex Turner’s been a little cagey about why Arctic Monkeys called this one “AM.” Is it a reference to the golden era of radio? The bleary morning hours? Is it a verb? Turner’s fielded this question a few times, with sort of a wry, noncommittal smile. The beauty of the title is that all of these feel possible. AM certainly marked the band’s shift to a more vintage flavor of rock and roll one might associate with AM radio. Turner certainly used this album to catalog his weary, glassy-eyed post-midnight, pre-dawn prowlings. And as a definitive statement, AM asserted the band’s staying power, the fulfillment of their enormous potential — not a “was” band or a “will be” band but an “am” band. It all kinda works.

This shifty attitude is matched by the album's instantly iconic cover. Rockstar sunglasses? A strapless bikini? Just a wavelength? Or yet another Rorschach Test suggesting that what listeners got out of AM largely depended on what they brought into it? Here, again, it doesn't feel like there's a wrong answer. Not when the album delivers on pretty much every promise you could read into it.

It’s a slinky, sultry ode to the LA underworld, a tension-filled, anxiety-soaked bruiser full of leather jacket sleaze, cigarette smoke, black lingerie and an embarrassment of atomically perfect riffs. “Do I Wanna Know?” kicks things off, a time bomb that never quite explodes but instead pulls everyone down into the late night club bathrooms and seedy hotels that make up the AM landscape. From there we go into “R U Mine?” a Sabbath-possessed headbanger that starts at eleven and does not let up for a single second of its three-and-a-half minute runtime. Most songs on AM fall into one of these buckets — tantalizing slowburn (Knee Socks, One for the Road) or incendiary release (Why Do You Only Call Me When You’re High?, Arabella).

Lyrically, Turner wisely pulls back a little from his earlier kitchen-sink approach. He’s more economical here, a fitting speed for the jaded, horny weariness that infects most of these songs. AM finds him less a seducer than a stalker, his rockstar insecurities giving his last call come-ons an ever-so-slight sheen of creepiness. “Why do you only call me when you’re high?” he moans. On “Knee Socks” he tells a girl that “you know who’s calling even though the number is blocked.” Slower, eerier songs like “Arabella” and “One For the Road” are like soundtracks to rifling through your one night stand’s medicine cabinet while she’s asleep in the other room.

It’s an act, of course, and Turner knows it. He’s no Mick Jagger and the Arctic Monkeys are no Rolling Stones. The mask slips on the cheekily named “Number One Party Anthem,” the closest thing AM has to a pretty song, where Turner finally admits that he’s tired of it all. The parties, the models, the booze, the drugs — it’s left him profoundly exhausted. AM is an album to fill arenas but its natural habitat is the lonely walk home, after the buzz fades but before the hangover sets in, when you start questioning your whole entire life.

Turner has said that AM was inspired by hip-hop, and that influence isn’t exactly obvious until you know what you’re looking for. It’s the way Arctic Monkeys string their monster riffs together with sparse, sinewy rhythms that ooze pop sensibility. It’s the album’s accessibility, the way these born-and-raised Brits enveloped their sound in something that feels distinctly American.

Maybe, in the end, the best explanation for AM is the simplest: the band’s initials. By the time AM dropped, Arctic Monkeys had spent ten implausibly good years as a band. Their record-shattering debut made them the UK’s answer to the Strokes, and their prolific few years of follow-ups established them as gifted shape-shifters who knew how to explore genres without sacrificing what made them tick. But AM felt like a second debut, an announcement of longevity. Arctic Monkeys were here to stay.

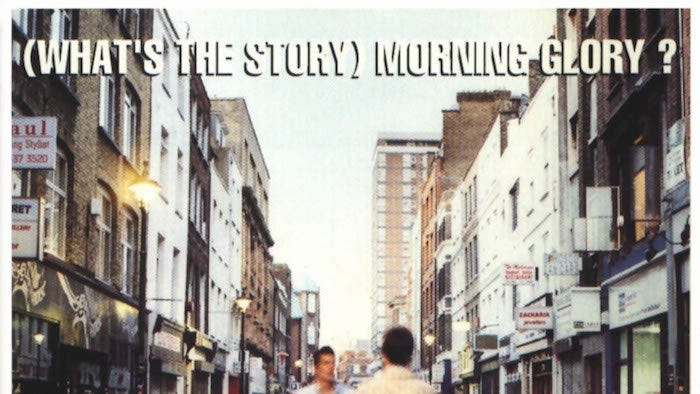

Day 58: Oasis — (What's the Story) Morning Glory?

When this album came out, the UK music scene stood at a crossroads: Blur or Oasis? The stakes were high, and represented two very different futures for Her Majesty’s empire. Blur were upper crust art-rock lads. Oasis were working class blokes. Blur were cool, fresh original artists. Oasis weren’t fixing what ain’t broke. Blur were savvy cross-genre navigators. Oasis were walking PR nightmares with legendary tempers. The two bands released their advance singles on the same day on August 14, 1995 and Blur’s “Country House” crushed Oasis’ “Roll With It” on the charts. It looked like England had made its choice, and Britpop would be shaped by Damon Albarn and Co. But that, as it turned out, was just the battle. "(What’s the Story) Morning Glory?" would become one of the defining albums of the 90s, not just in England but, crucially, here in the U.S. as well. No offense at all to Blur, who I love, but Oasis clearly won the war.

A lot of What’s the Story’s dominance can be chalked up to the lingering omnipresence of a handful of its tracks. The cigarette lighter glow of “Champagne Supernova.” The heartfelt (and ironic, given the band’s subsequent estrangement) beer can balladry of “Don’t Look Back in Anger” (a noted favorite of friend of the substack Al Hunter, whose many excellent playlists are available in Lo Fi, which you can buy wherever fine books are sold). And the big one, that big one, the song that will be echoing in the karaoke bars of Heaven for eternity. Nobody can tell you exactly what it means to be someone’s wonderwall after all, but we all feel what it means in our hearts.

Your heart is where you listen to an Oasis song. They mastered the art of the campfire singalong, writing music that makes you want to pump your fist in the air and match Liam Gallagher’s freak. Their Atlantic-crossing success can be attributed at least in part to this heartland rock energy they tapped into. But they did it without sacrificing an inch of the Britishness that you can hear on every inch of What’s the Story?, from Liam’s nasal bleating to the line on “She’s Electric” about how he “quite fancies her mother.” So many Britpop bands achieved success by checking their Britishness at the door. Oasis had no intention of doing so and would have socked anyone who suggested they try.

What’s the Story’s legacy rests on its gargantuan singles, but the album has some real pleasures in its deeper cuts (or, at least, as deep as an album as big as What’s the Story can claim to have). “Casts No Shadow” is a moving ode to Richard Ashcroft, who was about to leave his own mark on the Britpop scene as frontman of The Verve. Album opener “Hello” does a great job of settle the table, a snarling rumination on the Gallaghers’ complicated feelings about becoming stars: “The years are falling by like rain and it’s never gonna be the same.” And I really love the title track, a coke-fueled tumble through London’s late night afterparties that proves these guys really could rock when they felt like it.

And they ended up not feeling like it much longer. The band made no bones about their desire to be as big as the Beatles, but their behind-the-scenes drama made the final days of the Fab Four look like the Partridge Family in comparison. Liam and Noel don’t talk or, at least, say they don’t talk. Their old rivals Blur would end up being a little more Beatles-like, at least in terms of a sonically adventurous spirit. But for a few years there, Oasis not only set a course for Britpop. They conquered the world.

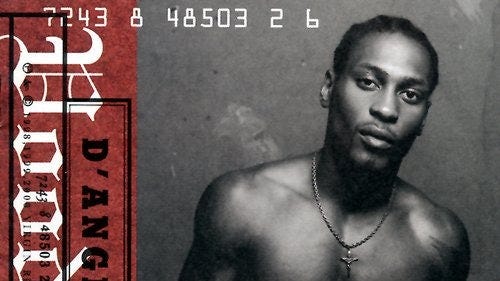

Day 57: D'Angelo — Voodoo

Originally, the thing that stuck was the music video. “Untitled,” a Prince-like sultry slow jam that featured D’Angelo, alone, shirtless, looking about as good as anyone has ever looked on film. The camera takes its time panning across his diamond abs and although he was actually wearing low slung sweatpants, the video definitely invites viewers to let their minds run wild. The video did its work. Voodoo, D’s long anticipated sophomore effort, went platinum in the early weeks of the new millennium and the man himself became a bonafide sex symbol. It also ruined his life.

"You've got to realize, he'd never looked like that before in his life," D's trainer Mark Jenkins told Spin in 2008. "To be somebody who was so introverted, and then, in a matter of three or four months, to be so ripped — everything was happening so quickly." D’Angelo’s live shows became manic, with thousands of ladies screaming at him to take off his clothes. Standard pop star stuff, especially in the early ‘00s. But D’Angelo wasn’t built like that. He wasn’t interested in fame. He hadn’t written Voodoo as a way to leverage his sex appeal. But Voodoo the artistic achievement was getting lost beneath D’Angelo the guy with a really good six-pack. By all accounts, all this contributed to his subsequent 14-year hiatus.

He left us with his masterpiece, one of the true masterpieces of the ‘00s. The brief neo-soul surge left us with an embarrassment of riches — Erykah Badu’s ‘Baduizm,’ Maxwell’s albums, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill, etc. But Voodoo was its crowning moment, the fullest realization of what this small and stupefyingly gifted collective of artists were capable of. By subbing warm, vintage sounds for the slick, club production that characterized the era’s soul, neo-soul artists bridged the gap between the new millennium and the era of Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Prince and Sly and the Family Stone. Voodoo was full of rich, layered, organic music from a crackerjack team of artists who’d made a study of Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield, but was also undeniably bleeding edge and in conversation with the Wu-Tang Clan and even Naughty by Nature. He recorded the album at Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Lady in New York, and he had Questlove on the drums and J Dilla in the booth. No other album of the neo-soul era sat as comfortably at the intersection of R&B and hip-hop.

D was a prodigious musical artist but he was deeply interested in spiritual wisdom. He was interested in people — how and why we meet, fight, fall in love, get hurt, forgive, have sex, betray each other and learn to trust each other again. Voodoo’s beguiling and surprising song structures match the wild and wonky nature of human relationships. Basically nothing in here is verse-chorus-verse-chorus-chorus. D wrote his songs intuitively, letting his voice ooze over the whip smart production naturally. You could listen to this album a hundred times and it’ll still catch you off guard with its professional spontaneity. It breaks the rules with the confidence of a guy who’s spent enough time with the rules to know exactly when and how they can be ignored.

It is the product of real genius, and I don’t use the term lightly. But also tortured genius, as D’s troubled time in the wilderness would show. But more recent years seem to have found him in a much healthier place. He released a fantastic follow-up in 2014, and has been at least somewhat visible ever since, collaborating with Jay Z as recently as this year. It took almost a quarter century, but D’Angelo the artist has finally escaped the shadow of D’Angelo the pinup. And thanks to the enduring legacy of Voodoo, he’s become what he was always meant to be: a legend.

56: The Cure — Disintegration

In 1989, Robert Smith found himself at a crossroads. As a frontman for the Cure, he’d had more success than any smalltown British goth weirdo could rightfully expect. Indeed, the Cure’s 1987 Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me had met with so much success that Smith was growing a little uneasy with his burgeoning pop star status. He didn’t want to be a pop star. He wanted to be a serious musician, and there was the rub. He was 29 years old. His heroes — Hendrix, Bowie, Alex Harvey — had all turned in their masterpieces in their 20s. The clock was ticking. Smith felt that if the Cure was going to be a band that would be remembered, it was time for him to make a memorable album. He made Disintegration.

Now, to be clear, I think Smith was being a little hard on himself. The Cure’s pre-Disintegration work includes stuff like “Boys Don’t Cry,” “Just Like Heaven” and “Friday I’m in Love.” Those are some eternal bangers, and I think starcrossed lovers would still be putting them on mixes today if Smith had hung up his career in ‘88. But he was right on this point: Disintegration is the Cure’s masterpiece.

As a former emo kid, I’m not really sure what anyone means by emo and I’m not sure they ever did, but I think they should mean Disintegration. Not in the sense that these songs have much in common with peak emo stuff like Hawthorne Heights or whatever, but in the sense that this music is expansively emotional in a way very few collections of songs are. It’s all here. If you come to Disintegration in a depressive state, it’ll meet you where you’re at. But if you’re just feeling overwhelmed or wistful or angry or in love, it’s got that going on too. Not only does it have all these emotions swirling together, but they are swirling in every direction, infinitely, like a vast sea. “Plainsong” is one of the most towering, gorgeous openers I’ve ever heard, and while the title refers to Gregorian chants, it also makes me think of the Great Plains where I grew up, vast land cast about you to the horizon in every direction. That’s what this album feels like: like you can see and feel everything all around you. It is a spectacular and astonishing listening experience.

Of course, that’s why this album became so associated with adolescence. It’s the sort of album, and the Cure was the sort of band, that a teenager could easily build their whole entire personality around. Kids started dressing like Robert Smith and hanging Cure posters in their bedrooms because being a teenager is when you feel most like you’re feeling everything everywhere all the time, which is the Disintegration experience. But listening now in the last year of my 30s, what sticks out to me is the album’s maturity too. Smith was very clearly feeling the end of his youth, which had him feeling some type of way. But he was also feeling a lot of grownup emotions that aren’t so bad. “Lovesong,” which marked the Cure’s only time on the U.S. top ten, was written as a wedding present for his highschool sweetheart Mary, who he’s been married to since ‘88. “The Same Deep Water As You” finds two people struggling to match each other’s relational freak. These topics aren’t necessarily foreign to the teenage experience, but they’re not the sort of things you associate with moody teen music. Part of the reason Disintegration was taken seriously by his adolescent fandom was that he took them seriously.

The other reason Disintegration was taken seriously is that it just rocks. The album is about 50 percent intro, with enormous synths unfurling underneath oozy guitars, godlike drums and those windchimes that spray across the soundscape like a smattering of stars. At first, these long, go for broke instrumental openers seem like tension-builders — when is he gonna start singing? — but then you accept the Cure’s invitation to just go with it and let it all envelope you. Smith doesn’t start singing until almost two minutes into “Pictures of You,” but the melody itself has already resolved into a comforting splendor.

It’s a lot, but it’s a lot in a deeply satisfying way. The album has a reputation for being gloomy, but that’s never been how I’ve thought of it. A few years back, I was at Lollapalooza when the Cure took the main stage, opening with “Pictures of You.” While I was there, my sister called to tell me that she was having a baby. Now, I can’t hear “Pictures of You” without thinking of my niece, Ruby. And if the Cure can make a song big enough to contain my feelings about that wonderful kid, I suppose their music must count among the biggest songs ever written. Albums don’t get much more memorable.