This is Clusterhuck, my newsletter about faith, culture and a flourishing future for all! I’m glad you’re here. I can only do this through the support of my readers, and I’m grateful for every one I’ve got. If you’d like to join, just click here. You’ll get a free seven-day trial, including access to all the archives.

I could write about a lot of things today. I don’t know if you watch the news, but there’s a lot going on. Much of LA is a smoking ruin. TikTok exists in a limbo between legal and not legal. Mark Zuckerberg has lost his marbles. David Lynch, my creative hero, is dead. And to top it all off, the horse is back in the hospital. Oofta woofta. God said there’d be Mondays like these.

But the thing I’m actually thinking about kind of addresses all these issues by addressing none of them. Two years before his death, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote an address for the inaugural Berlin Jazz Festival. It’s short and very beautiful.

“God has wrought many things out of oppression,” he began.1 “He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create—and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed man to cope with his environment and many different situations.” Hopefully, you’re already seeing this speech’s relevance.

He continued:

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life’s difficulties, and if you think for a moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph. This is triumphant music.

Modern jazz has continued in this tradition, singing the songs of a more complicated urban existence. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument.

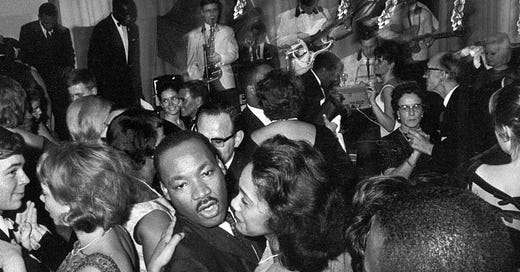

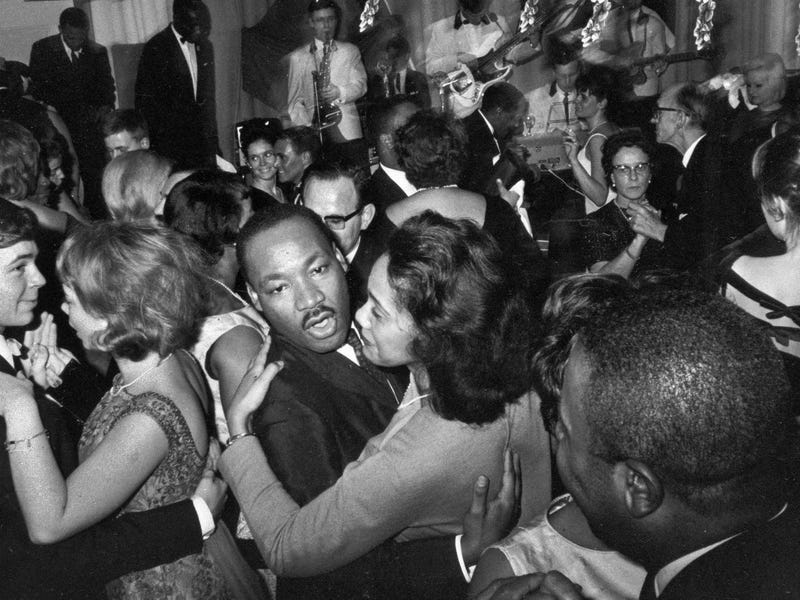

At the time, both MLK and jazz music were enjoying a high international profile. King had just been named Time’s Person of the Year2 while jazz was being deployed as a global branding tool. Pictures of the Civil Rights struggle were spreading around the world, thrusting the oppression of Black men and women into the international spotlight. The U.S. would later accuse the Soviet Union of using these images as anti-American propaganda but, well, is it “propaganda” if it’s just a picture of something that was actually happening?

But jazz was also spreading. John Coltrane, Charles Mingus, Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock were already cultural icons, and the image of them playing in nightclubs, Ivy suits behind a smoky haze, was about as cool as an American could be (still is, in my opinion!)3. Eisenhower had launched a Jazz Ambassadors program through the State Department a few years earlier in hopes that recruiting a few of these guys to his team would soften the global image of America. It was a qualified success, partly because his first official Ambassador, Dizzy Gillespie, wasn’t particularly interested in playing by the rules. When the State asked him to come in for a briefing on how to talk about racism abroad, Dizzy’s response was curt: “I’ve got three hundred years of briefing. I know what they’ve done to us.”

But the images of jazz can’t really compare to the jazz itself. I only got truly jazz-pilled last year. My jazz intake was mostly limited to the entry level classics — your Bitches Brews and Kind of Blues — until I picked up Eastern Sounds, Yusef Lateef’s 1962 hard bop/middle eastern fusion. It’s not the most obvious point for jazz awakening, but it worked like gangbusters on me, and jazz has since swallowed my music listening habits whole. And now, after roughly a year-long deep dive into jazz, I’ve got to say, I’m glad to have it around for the days ahead.

A lot of the “self care” talk from Trump’s first time at bat centered around rest — making time to take walks and play with the dogs so that you don’t burn out from too much caring. I think there’s something to that (and wrote as much last week), but I appreciate how King saw art as not just a source of rest, but also as a source of energy. “Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music,” he wrote. “It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.”

For King and, indeed, for much of the Civil Rights Movement at large, the creative life was not just what you did when you weren’t marching for freedom. Jazz music4 was part of the work, both fuel for the fire and water in the desert.

Notably, King did not here make a distinction between jazz that was explicitly about the freedom movement and jazz that wasn’t. It’s certainly true that some jazz songs took on the issue Civil Rights directly, such as Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddamn” and John Coltrane’s “Alabama.” But King’s speech implies that the strengthening power of jazz can also simply come from creative expression in and of itself. This, I think, is a good reminder for artists tempted to make liberal spins on God’s Not Dead-style choir preaching on the evils of Trumpism over the next four years. Better a good piece of art about nothing in particular than a bad piece of art about a noble cause.

King did not actually attend the Berlin Jazz Festival in ‘64. If he had, he would have seen the likes of George Russell, Coleman Hawkins, Roland Kirk, Dave Brubeck, Joe Turner, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Miles Davis himself. Not a bad lineup. Your dream creative roster of 2025 will look quite a bit different. It might not be jazz. It might not even be music. But you’ll need something for what’s ahead. “Everybody has the Blues,” King concluded. “Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith. In music, especially this broad category called Jazz, there is a stepping stone towards all of these.”

Your stepping stones might not necessarily be jazz (although, like MLK says, you could do a lot worse), but the important thing is to have those stepping stones. If you want to be of any real, practical use over the next four years, you’re going to need them.

Losing David Lynch messed me up, man. It really did. I don’t really feel up to the challenge of writing about his work or what it meant to me, but I gave it my best stab at RNS.

It was a bit tricky to write about Lynch for an outlet called Religion News Service, because Lynch was the blueprint for the “spiritual but not religious” guy. But his work, to me, is about as morally serious as movies get, so if religion and morality meaningfully intertwine in your own life, you might find it interesting.

One thing I’ve been thinking about a lot over the last few days was Laura Palmer’s trajectory in Twin Peaks. She started out as a lifeless body “played” by Sheryl Lee, little more than a prop to set the events of the show in motion — same as so many other stories that kick off with a dead blonde. But over the arc of Twin Peaks, Lynch strained to give Laura more dignity in death than her friends and fellow citizens ever had in life. And then, finally, in Fire Walk With Me, he accomplished a creative rugpull for the ages, indicting both the town of Twin Peaks the the American viewership who’d made the show a hit for caring more about the whodunnit than the human victim at the heart of it. He read the true crime craze for filth years before it actualized.

In closing, here’s my ranking of Lynch’s movies:

10. Dune: I don’t love it but it’s not as bad as its reputation.

9. Inland Empire: My pick for his least accessible movie. Dern’s finest hour.

8. Eraserhead: A dark, singular nightmare about the mortal terror of accidentally knocking up your girlfriend.

7. Lost Highway: Lynch at his scariest. I read it as a reaction to the OJ Simpson trial.

6. Wild At Heart: Lynch at his most jubilant. His happiest ending.

5. Elephant Man: Lynch famously said Eraserhead is his most spiritual film. I think it’s this one. You be the judge.

4. Blue Velvet: A real BC/AD moment in American filmmaking. Love it or hate, ya gotta watch it.

3. Straight Story: Miracle of a movie. Both in line with everything else he’s done and unique in its tenderness and gentle melancholy.

2. Fire Walk With Me: So glad Lynch lived to see the culture come around on this one.

1. Mulholland Drive: What can you even say about it? One of the best movies ever made, full stop.

AND FINALLY: Got an announcement coming later this week, when all the inauguration stuff has died down a little. It probably won’t impact your life much but it does have some ramifications for this Substack that my subscribers will want to be aware of, so stay tuned!

Love how easy it is to mentally transpose King’s writing to his speaking voice. He did not actually ever deliver this writing as a speech, so far as we know. But you can hear him shouting “God has wrought many things out of oppression” in your head anyway.

So today isn’t the first time Trump and King had to share a platform.

G. Bruce Boyer has done a lot of writing on the intersection of jazz and American fashion, and he’s of the mind that the Ivy-inspired fashion of mid-century jazz musicians was hugely instrumental in their popularity. His book Riffs is a fun read — part musical coming-of-age memoir, part American music history lesson, part menswear guy-type posting.

And other creative expression of Black artists at the time, such as the poetry of Gil-Scot Heron and Langston Hughes, the writings of Ntozake Shange and James Baldwin, and the paintings of Faith Ringgold and Alma Thomas.