Lessons on Life Under Siege From 'The Great Escape'

John Sturges' wartime classic as an instruction manual for the next four years.

This is Clusterhuck, my newsletter about faith, culture and a flourishing future for all! I’m glad you’re here. I can only do this through the support of my readers, and I’m grateful for every one I’ve got. If you’d like to join, just click here. You’ll get a free seven-day trial, including access to all the archives.

I needed some escapism the other night so I popped on The Great Escape. It was an Amelia Bedelia-ass decision but that doesn’t make it wrong. In fact, it turned out to be absolutely correct. I had a blast watching the boys escape. And while I’m definitely taking in everything through a political filter right now, it gave me more electoral meat to chew on than I expected. Not so escapist after all.

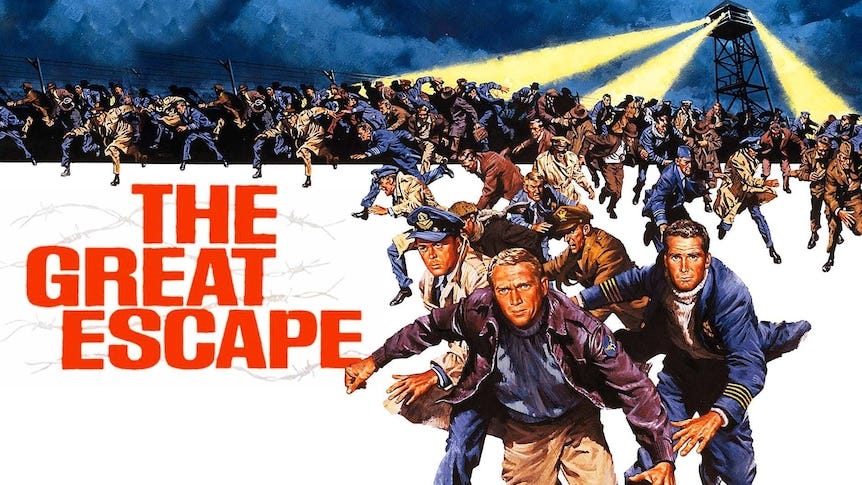

I don’t really need to bother with much background for a classic that casts a shadow as long as this one, but just in case: The Great Escape is John Sturges’ epic about the true(ish) story of a group of WW2 POWs who made a break from a Nazi prison camp. It’s largely based on Paul Brickhill’s first-person account of the escape, but Sturges took a lot of liberties with the material. Most notably: virtually no Americans were involved in the escape plan or the escape itself. Most of the POWs were British, and Brickhill himself was Australian. But this was the early 60s. Hollywood’s Golden Age was in full bloom, and the thinking was that a movie couldn’t really succeed if it wasn’t teeming with Americans. Thus you have guys like James Coburn, James Garner, Charles Bronson and, of course, Steve McQueen, in his breakthrough role.

But what The Great Escape loses here in historical accuracy it gains in one of my favorite dynamics of all time: British class bumping up against American swagger. This movie really makes a meal out of these two energies, mostly ignoring the potential for conflict in favor of showing what’s possible when Her Majesty’s gentlemen and Lady Liberty’s cowboys join forces.

Brickhill’s book was a hit upon publication and spawned a successful stage play, but no movie studio wanted to touch the story because (spoilers for a 60-year-old movie based on an 80-year-old event) it’s a real downer. There is no happy ending. The Great Escape is ultimately foiled. Of the 76 men who escaped the Stalag Luft III prison camp, 50 were killed and 23 were recaptured. Only three actually made it across the border to Switzerland. The Great Escape is as classic as Hollywood movies get, but it does not have a classic Hollywood ending.

But that’s part of what makes the movie such a rich text for these times. Don’t get me wrong: I’m not about to compare my life under Trump 2.0 to life in a Nazi prison camp. Stephen Miller is a bad person, but he’s not Himmler1. But insofar as The Great Escape is about life under the rule of people who despise you and want you to despair of ever being free of them again, this movie has a lot to offer. Here are a few things I took away from it.

Don’t Surrender in Advance

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to clusterhuck to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.