How Nightcrawler Made Me a Better Christian

The X-Men finally gave us a hero who takes faith seriously without losing their sense of fun and adventure.

This is Clusterhuck, my newsletter about faith, culture and a flourishing future for all! I’m glad you’re here. I can only do this through the support of my readers, and I’m grateful for every one I’ve got. If you’d like to join, just click here. You’ll get a free seven-day trial, including access to all the archives.

X-Men post! Cue the theme! MAESTRO!

There’s a fascinating episode of the old 90s animated X-Men series that I’ve thought about more than any other single TV show. It’s called “Nightcrawler” and if you’ve followed my work for a while, you know I’ve written about it before. It’s a big part of my personality. The first time I saw it, I was something like nine years old at my grandparents’ house, sitting slack-jawed in front of the tv screen, forgotten breakfast cereal getting soggy in the milk.

This episode follows a small group of X-Men on a mountain skiing trip in Germany. Cajun raconteur Gambit and southern fried wildflower Rogue are hanging out with an even grouchier-than-usual Wolverine when they happen upon an old monastery which includes its order Kurt Wagner — the Nightcrawler. He’s got fuzzy blue skin, two-toed feet and three-fingered hands, and a point, prehensile tail. He looks like a demon, and has spent his life treated as such by the pitchfork-wielding peasantry that seem to populate X-Men comics.

But appearances can be deceiving, and nowhere more than in X-Men. It turns out that far from being a demon, this mutant — who can also teleport in a flash of smoke and sulfur — is a devout Christian. He spends most of this children’s episode debating Augustinian theology with Wolverine.

“What kind of God would let man do this to me?” Wolverine growls, brandishing the adamantium claws that were grafted over his bones as part of a top secret government experiment (comics!).

“Our ability to understand God’s purpose is limited,” Nightcrawler says. “But we take comfort in the fact that His love is limitless.”

“God gave up on us a long time ago,” Wolverine shoots back.

“God does not give up on His children,” Nightcrawler responds. “He is there for us in times of joy and when we are in pain, if we let Him.”

In another lovely speech, Nightcrawler tells Wolverine that “people of every faith believe there is a God who loves them! Can so many be wrong? Open your heart, Herr Logan. Would it hurt so much to see the world through different eyes?”

Pretty heady theology for a cartoon about superheroes! It was a little dizzying as a kid, to hear the sort of dusty old Bible schools lessons you’re used to on Sunday morning coming from spandex-wrapped mutants on Saturday. But the comic book source material has always punched above its thematic weight (sometimes more successfully than others). And it’s mostly through the comics that my lifelong love of this character has been cultivated.

A little background. Introduced in 1975 by writer Len Wein and artist Dave Cockrum as part of a soft reboot of the flagging X-Men superhero comics title, Nightcrawler was one of Marvel’s first heroic mutants to actually look like something had mutated.

The core concept of the X-Men is that a sizable percentage of the human race carries the “X-Gene,” which mutates them into the next stage of evolution. These “mutants” are hated and feared by most of humanity. A powerful telepathic mutant named Charles Xavier recruits some mutants as his X-Men, to help orchestrate his dream of equality. Others, like Magneto, are more interested in liberating mutants from their human oppressors by any means necessary. (While the early era of X-Men stuck firmly to a “Professor X = good / Magneto = bad” formula, these simplistic boundaries have been troubled and even inverted over the years).

While most of the previous heroes’ mutant powers were either cool (Iceman’s freezing powers) or beautiful (Angel’s wings) and allowed them to pass for humans in public, Nightcrawler actually looked different. It was a big leap forward for a series that had always ostensibly been about a marginalized group.

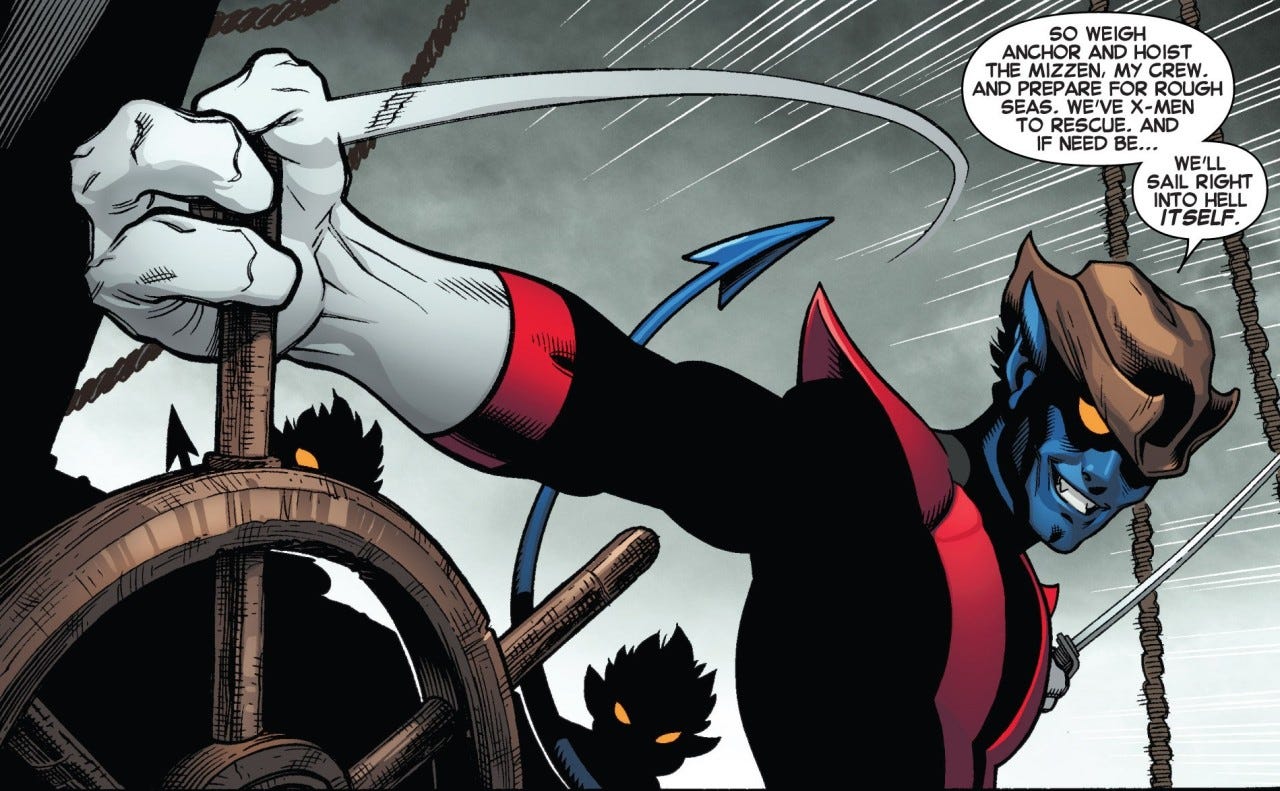

Despite his eerie appearance and alienation from humans (and even some other mutants) who were repulsed by his appearance, writer Chris Claremont quickly established Nightcrawler as the most fun-loving and adventurous of the new team. A former circus acrobat, he idolized Errol Flynn and fancied himself a swashbuckler in his vein, leaping into action with a daredevil grin and his telltale burst of smoke and trademark “BAMF.”

Unlike Wolverine, Nightcrawler’s not exactly spoiling for a fight, but he loves to rescue damsels. Nightcrawler is very big on damsels. While most superhero comics wade into love and sex with their mix of broody grouches (Batman), pure-hearted homeschoolers (Captain America), awkward dorks (Spidey), and the beautiful women of disastrous taste in men who fall for them, Nightcrawler is a silver-tongued romantic. It’s not at all hard to see why women might fall for the guy, prehensile tail aside (or …maybe not).

It was only later that Claremont would introduce a note of Catholic piety to Nightcrawler’s characterization. Over the years, he would frequently serve as the team’s spiritual mentor, and would even join the priesthood (a plot point which would later turn out to be a dream, but the less said about that, the better).

But generally, the animated series foregrounded Nightcrawler’s religion to a greater extent than the comics did. In the episode “Bloodlines,” Nightcrawler learns that his birth mother is the villainous Mystique, and that she abandoned him at birth.

“Still sad for me?” she glowers.

“I will beg God to bestow His grace on me so that I may learn to forgive you,” he says. “Then I will ask him to bestow grace on you, so that you might forgive yourself.”

What we are left with are two very distinct Nightcrawlers. The first is the dashing, fun-loving would–be buccaneer he was introduced as. The second is the devout disciple we met on the animated series, and only a little less frequently in the comics. Comic book writers have clearly struggled to integrate these two into one, seamless character. But it made sense to me.

When you’re a kid, pop culture representation of Christians is limited to either nerdy do-gooders like The Simpsons’s Ned Flanders, overbearing hypocrites like Hunchback of Notre Dame’s Claude Frollo or wizened mystics like The Count of Monte Cristo’s Abbé Faria. There’s a lot of Christian representation in America, but most of it is pretty bad and not really recognizable to your average youth group kid. But in Nightcrawler, I found what I was looking for. Here was a superhero who seemed to genuinely like being a Christian and took it seriously, but was also a fiend for a good time, a trusty drinking buddy for Wolverine and flirty to a fault. Unlike the animated series, the comics rarely put Nightcrawler and Wolverine at odds. The two have one of the strongest bonds in the X-franchise, and their differing opinions about spirituality and what comes next was just one more thread in their friendship.

He was, in other words, someone I could both see myself in and aspire to be.

Later writers like Si Spurrier would be more successful at weaving these traits into a singular whole. These writers could see that far from being opposing traits, there’s nothing so strange about being both deeply religious and a party animal. In the same way that Jesus’ first miracle was making sure there was enough wine to go around in Cana, Nightcrawler’s faith started to inform his sense of fun and adventure. His expressions of spirituality got less self-consciously devout and more mischievous.

There’s a scene from 2019’s House of X/Powers of X by writer Jonathan Hickman and artist Pepe Larraz that is one of my favorite scenes in superhero comics, and one that best captures his whole thing. He’s on a doomed spaceship with Wolverine, whom he’s about to teleport outside the spaceship on a joint suicide mission to destroy a giant robot.

WOLVERINE: So … I gotta ask … You still think there’s something waiting for us on the other side?

NIGHTCRAWLER: Worried about your soul, Logan?

WOLVERINE: Just wonderin’ what someone like me should expect.

NIGHTCRAWLER: When you wake from this earthly slumber, my friend, look for me. I will be there waiting for you. Radiant and with open arms.”

This is the depiction of faith that has captured me and, I think, probably helped make me better. In this framework, Christianity isn’t a cudgel to determine who’s in and who’s out. It’s not a wet blanket. It doesn’t exist in opposition to a spirit of adventure, but as a companion to it. It doesn’t get in the way of fun, but heightens it. It’s a source of encouragement and comfort, not just for the practitioner, but for the people who love them.

I’m guessing the reason we don’t see this sort of Christian representation in more media is pretty simple: there’s just not a lot of this type of Christian out there. But that doesn’t mean there can’t be, or shouldn’t be. Would it hurt so much to see the world through different eyes?

I love all the other articles, but this is the sweetest spot for me. Just like no X-Man is every really dead, I'm hoping for a resurrection of Cape Town.